I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

First time reading? Sign up here. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today's read: 13 minutes.

One year ago today: We were covering... the Supreme Court! The beginning of the Supreme Court's historic term, that included the challenge to Roe v. Wade and other major cases.

Correction.

In yesterday's quick hits section, we noted that the debt had passed $21 trillion for the first time ever. In fact, the debt passed $31 trillion. Nothing exciting here: the "2" and the "3" are next to each other on the keyboard, and this was just a typo that slipped through.

This is our 68th correction in Tangle's 165-week history and our first correction since August 16th. I track corrections and place them at the top of the newsletter in an effort to maximize transparency with readers.

"G-d."

I got a lot of emails from readers yesterday inquiring about why I did not spell out the word "God" in the newsletter. Many of them were kind and friendly notes, folks just curious about whether it was intentional or had meaning (it does!). However, some actually unsubscribed, and accused me of "censoring" the word... This surprised me, because I've done it a few times before in Tangle — and though a handful of folks have noticed, yesterday was a whole other animal.

Anyway, fun fact: Not spelling out G-d is a custom among some Jews that comes from the Torah’s prohibition on erasing G-d's name. The original idea is that writing the name in full could lead to it being disrespected (say, if you threw out the piece of paper, or later had to erase what you wrote). As with basically everything in Judaism, there is quite a bit of debate over it: Does such a prohibition apply to Hebrew only or also English? Does it apply to digital publications as well as paper? There are all sorts of other interesting dilemmas. You can read more about the custom here.

For whatever reason, I personally have always liked it for the respect it shows. We all attach ourselves to certain traditions, and this was one that resonated for me. So, no, I was not "censoring" or "disrespecting" G-d (perhaps you are seeing ghosts?) I was just practicing a modest custom many other Jews before me have — one that is actually meant to show a great deal of reverence for the word.

Tomorrow...

Our midterm coverage begins. This month, we're going to be focusing our Friday editions on topics related to the midterm elections on November 8th. As always, this is a great time to spread the word about Tangle (on Facebook, Twitter, or via email). We'll be kicking things off tomorrow with a table-setting piece: Where things stand, what races to watch, what the dynamics of the election are, and other things you need to know. Keep an eye out, and remember to share.

Quick hits.

- OPEC+, the coalition of oil producers that the U.S. is not a part of, announced it is planning to cut two million barrels of oil production a day starting in November in an effort to increase the price of oil. (The cuts)

- SpaceX launched four new crew members to the international Space Station alongside NASA, the sixth time it has done so under a NASA contract. (The launch)

- New FBI data shows murder rose by 4.3% in 2021, while overall violent crime fell by 1%. However, roughly half of U.S. police agencies, including those in Los Angeles and New York City, have yet to submit their data. (The numbers)

- The United States redeployed an aircraft carrier to the waters near the Korean Peninsula after North Korea fired two ballistic missiles over Japan. (The launch)

- A federal appeals court affirmed a ruling that DACA was illegal and blocked new applicants. However, the court also left it in place for existing "Dreamers" and called for a lower court to review the program for changes. (The ruling)

Our 'Quick Hits' section is created in partnership with Ground News, a website and app that rates the bias of news coverage and news outlets.

Today's topic.

Merrill v. Milligan (and its companion case, Merrill v. Caster). On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Merrill v. Milligan, a case that could have an impact on the Voting Rights Act.

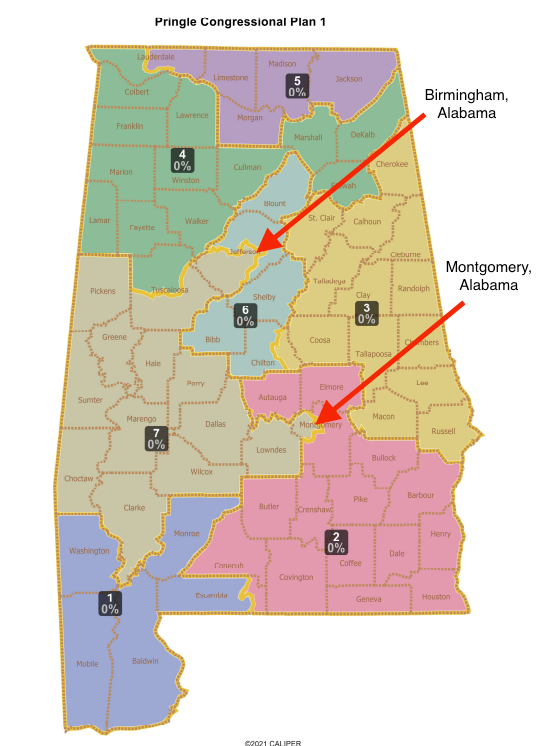

The background: Alabama has seven seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 2021, shortly after the 2020 census, the Republican-controlled legislature released its new maps for those districts. The maps were similar to the ones drawn in 2010 and 2000. However, despite 27% of the state's residents being Black, only one of the seven districts (~14%) in the map is majority Black. A group of registered voters, the NAACP and a multi-faith organization in Alabama filed a lawsuit over the map, saying it violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which bars a denial or abridgment (curtailment) of the right to vote based on race.

In their case, the plaintiffs argued that the state illegally gerrymandered as many Black voters into a single district as possible, while dispersing the remaining Black voters across the other six districts, effectively diluting their voting power. Instead, the plaintiffs argue, there should have been two congressional districts where minority voters were a majority (for an explanation of gerrymandering, see our previous coverage).

A three-judge panel, including two judges who were appointed by former President Trump, agreed that the map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The state filed an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court to freeze that ruling, which it did, allowing Alabama to move forward with its current map for the 2022 primary and general elections. Then the Supreme Court set a date to hear the case. Oral arguments began on Tuesday.

The arguments: Alabama is arguing that Section 2 does not mean the state is obligated to draw a majority-minority district anywhere it can be drawn, especially when you have to sacrifice race-neutral redistricting criteria to do so. The state says that interpreting Section 2 to require the state to create another majority-Black district would violate the Constitution, precisely because it would create a race-based targeting and sorting process, which would violate the 14th and 15th amendments.

Instead, the state says the question is if the political process is "equally open," and it argues that its map was drawn using race-neutral redistricting criteria, including a goal to draw lines as close as possible to previous districts. In order to change the map, the state argues the plaintiffs must be able to draw lines that create a second minority-majority district without prioritizing race, something the plaintiffs have struggled to do.

On the other side, the plaintiffs argue that Section 2 has a limited but important role, and that it requires consideration of race when "pervasive racial politics would otherwise deny minority voters equal electoral opportunities.” The plaintiffs maintain that decades of precedent demonstrate race plays a role in determining when a redistricting plan violates the Voting Rights Act.

Additionally, the plaintiffs argue that citing Section 2 does not violate the constitution as it is currently written. It argues that a state does not violate Section 2 by failing to create as many majority-minority districts as possible, and no such standard has ever existed. If the justices are concerned about how Section 2 is being applied, the plaintiffs argue, they could reinforce the limits of how it should be tested, not "jettison the standard" entirely.

In play are previous Supreme Court rulings. In 1986, in Thornburg v. Gingles, the Supreme Court created a multi-part test to determine if Section 2 was being violated via vote dilution. That test includes questions like whether a minority group is big and compact enough to form its own district, or if the "totality of circumstances" indicate it’s violating the Voting Rights Act. Chief Justice John Roberts justified taking up this case, in part, because the Gingles standard has created "considerable disagreement and uncertainty" with vague and tests that are difficult to apply, which he wants the court to revisit.

In Tuesday's oral arguments, it appeared the court was going to side with Alabama, allowing the maps to stand, but seemed skeptical of making a far-reaching change to Section 2 or the Voting Rights Act. Today, we'll explore some arguments from the left and right, then my take.

We'll be skipping today's reader question to give this story space.

What the left is saying.

- The left argues that this is an attempt to destroy the Voting Rights Act, and amounts to another attack on democracy.

- Some applaud Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson for her originalist arguments against Alabama.

- Others hope the court will avoid a drastic ruling that would be disastrous for voting rights.

In The Washington Post, Katrina vanden Heuvel said the Supreme Court was "reconvening its assault on democracy."

"The Voting Rights Act, one of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s greatest legacies, is a prime target," she wrote. "Five conservative justices joined in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder to gut the act’s core enforcement mechanism: the requirement of prior federal approval for voting changes in states with a history of discrimination. Writing for the court, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ignored the detailed record — and common sense — to make his own finding that racial discrimination was no longer a problem in the United States.

"Now, the act’s prohibition of voting practices that result in 'denial or abridgement' of the right to vote on account of race is at risk. Merrill v. Milligan involves an Alabama redistricting plan that ensures that African Americans, who make up more than one-fourth of the state’s population, will constitute the majority in just one of its seven congressional districts," she said. "Having engaged in blatant racial gerrymandering, the state of Alabama now argues that race can’t be used as a factor to draw up a fairer map.

In Vox, Ian Millhiser said it looks like the court is ready to weaken, but not destroy, the ban on racial gerrymandering.

“Republican appointees Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett both pointed out that [Alabama Solicitor General Edmund LaCour's] proposed reading of the Voting Rights Act cannot be squared with the law’s text,” Millhiser wrote. “Even Justice Samuel Alito, the Court’s most reliable partisan, acknowledged that LaCour offered some proposals that are ‘quite far reaching’ and others that are more ‘basic,’ and he seemed to urge LaCour to stick to his more ‘basic’ ideas. None of this means that Alabama is likely to lose this case.

“But several of the justices, including Roberts, Barrett, and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, seemed to spend the morning casting about for a way to rule in Alabama’s favor without explicitly overruling nearly four decades of established voting rights law stretching back to the Court’s decision in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986),” Millhiser said. “Based on oral arguments Tuesday, the most likely outcome in Merrill is a narrow decision for Alabama, bailing out the maps drawn by the state’s Republican-led legislature, but holding off for another day the question of whether to legalize many forms of racial gerrymandering en masse.”

In Slate, Mark Joseph Stern argued that Ketanji Brown Jackson used originalism to effectively pierce the state's argument.

“For decades, conservative justices have made a specific point to support many of their rulings on race: They insist that the Constitution is entirely ‘colorblind,’ prohibiting any consideration of race under all circumstances," Stern wrote. "In a series of extraordinary exchanges with Alabama Solicitor General Edmund LaCour, Jackson explained that the entire point of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments was to provide equal opportunity for formerly enslaved people, using color-conscious remedies whenever necessary to put them on the same plane as whites. It was a masterclass in progressive originalism that illustrated exactly why Jackson is such a crucial addition to this ultra-conservative court.

“Jackson went on to note that one purpose of the 14th Amendment was to provide a constitutional foundation to the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which 'specifically stated that citizens would have the same civil rights as enjoyed by white citizens.'... Jackson is plainly correct: The Framers of the 14th Amendment (which guarantees equal protection) and 15th Amendment (which bars race-based voting discrimination) explicitly supported race-conscious remedies to civil rights violations,” Stern wrote. “They intended the post-Civil War amendments to guarantee equal opportunity to Black citizens, combatting ‘deep rooted prejudice of the white race’ against Black Americans to help them secure a ‘just and constitutional position.’ As legal historians have persuasively explained, the Framers readily took race into account when necessary to redress past discrimination.”

What the right is saying.

- The right hopes to see Alabama prevail, arguing that the current precedent is convoluted and difficult to apply.

- Some say the plaintiff's argument amounts to precisely the kind of racial prioritizing that is prohibited by the Constitution.

- Others criticize Justice Jackson's "faux originalism."

The Wall Street Journal editorial board asked, "Gerrymandering strictly by race is illegal, so how can it be required?"

“Alabama has seven House seats, so one majority-black district comes out to 14%, while 26% of the state’s voting-age population is black,” the board wrote. “A federal court said in January that Alabama is required by the Voting Rights Act (VRA) to create a second majority-black district, which would be 29% representation. Is this the law, or is it another misguided effort in what Chief Justice John Roberts once called a ‘sordid business, this divvying us up by race’? Section 2 of the VRA bans voting practices that aren’t ‘equally open’ or that give racial minorities ‘less opportunity’ to ‘elect representatives of their choice.’

“The High Court has blessed claims of vote dilution, with the operative precedent being Gingles (1986). It sets forth a multipart test: Is the minority group big and compact enough to be its own district? Is it politically cohesive? Is a VRA violation indicated by ‘the totality of the circumstances’? On the other hand, Section 2 explicitly says it doesn’t create any sort of ‘right to have members of a protected class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the population,’” the board notes. “More recent Supreme Court rulings have said gerrymandering by race is ‘odious,’ and so strict scrutiny applies if it’s a ‘predominant’ factor for mapmakers... What distinguishes a district favoring black voters, who happen to be Democrats, from a district favoring Democrats, who happen to be black?"

In The Wall Street Journal, James Piereson said the Supreme Court has a chance to "reaffirm" the colorblind ideals behind the Voting Rights Act.

"Alabama argues that the plaintiffs drew their map using a racial outcome as the main goal, a practice the Supreme Court has discouraged in previous cases. The plaintiffs’ proposed new district runs from one side of the state to the other, fractures local communities, and cherry-picks voting precincts with black majorities to ensure the election of a black representative," Piereson wrote. "Congress passed the Voting Rights Act to protect minority voters by banning literacy tests, overly cumbersome registration requirements and the like... But the Supreme Court soon expanded the act’s reach to cover election rules and the drawing of districts.

“As a result, the Supreme Court has wrestled for decades with redistricting issues. In Gingles v. Thornburg (1986), the court advanced a vague multi-step test to demonstrate dilution of minority votes: A minority group must show that it is sufficiently large and compact to form a majority in a single-member district, and it must show that blacks and whites vote cohesively in opposite directions. These claims, if met, would entitle the group to one or more minority-majority districts,” Piereson said. “But it appears likely that the court is ready to revisit these tests. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have argued that Section 2 of the VRA refers only to barriers to voting and doesn’t extend to redistricting or claims of vote dilution. That approach, if accepted by a majority, would foreclose most such litigation. It would also be consistent with the language of Section 2, which bans state-enforced barriers to voting on account of race.”

In National Review, Carrie Campbell Severino and Frank Scaturro called Justice Jackson's arguments "faux originalism."

“Justice Jackson’s position seems to be that line-drawing based on race is not only permissible but required under the law. She asserted that the Framers adopted the 14th Amendment’s equal-protection clause and the 15th Amendment ‘in a race-conscious way.’... the record is clear that Congress was working to remedy flagrant racial discrimination under the law — particularly the discrimination of the Black Codes in the former Confederate states, which aimed to relegate those who had been emancipated to a status that closely resembled slavery,” they wrote. “The very remedy employed by Congress to override the Black Codes was the Civil Rights Act of 1866, for which the 14th Amendment was meant to provide a firm constitutional foundation.

"Jackson cited this law without acknowledging that it was actually meant to eliminate racial distinctions," they said. "Even putting aside the whites who received rations from the Bureau, it is clear that benefits targeting formerly enslaved people — in a country where the institution of slavery was race-based — would go to African-American recipients based not on their race, but on their past enslavement. To remedy that was not to create any new racial category in the law. The debates over the Reconstruction amendments and the laws meant to enforce them are filled with statements by supporters of those measures articulating the intent of abolishing racial distinctions in the law. That included the most prominent supporter in the House of Representatives, Thaddeus Stevens, who, during debate over the Civil Rights Act described as 'the genuine proposition . . . the one I love’ that ‘all national and state laws shall be equally applicable to every citizen, and no discrimination shall be made on account of race or color.'"

My take.

Reminder: "My take" is a section where I give myself space to share my own personal opinion. It is meant to be one perspective amid many others. If you have feedback, criticism, or compliments, you can reply to this email and write in. If you're a paying subscriber, you can also leave a comment.

- Irrespective of this case, what Alabama's legislature has done should be illegal.

- The particulars of this specific case are complicated, and a narrow ruling for Alabama may be justified.

- However, the entire ordeal is — more than anything else — evidence of the cracks in our democratic system that must be remedied.

Before getting into the merits of the legal arguments here, I just want to say unequivocally that Alabama's map should be illegal.

If you've read my writing about gerrymandering before, that opinion won't be a surprise to you. As has become common across the United States, it's clear to me that the Alabama state legislature is picking its voters, not the other way around. Gerrymandering is the most obvious threat to democracy there is. It isn’t unique to Republicans or Alabama, but it’s definitely what’s happening here. The Alabama legislature’s map is clearly not a good-faith attempt to draw fair maps or ensure Alabama voters are represented equally — it’s gerrymandering.

The primary defense of this map — that it adheres to previously drawn lines — is rather infuriating if you think about it for a minute. Given Alabama's sordid history of diluting Black votes and discrimination against Black voters, of course a map that stays true to previous lines is still a kind of racial gerrymandering. It’s true previous lines are one of many criteria for drawing new lines, but it’s not true that adhering to them absolves these lines from racial discrimination. In fact, the opposite is closer to true.

Again: The lower court panel, which included two bonafide conservative judges appointed by former President Trump, spent 225 pages explaining that they did not view the question of whether Alabama violated the Voting Rights Act to be “a close one.”

Whether it's the absurd looking maps in New York drawn by Democrats or these maps in Alabama (below), let's please not pretend it's some great mystery about what's going on. To make this simple, just look at the shape of the 7th district, and where Montgomery and Birmingham, two of Alabama’s three largest cities, both of which are predominantly Black, are located:

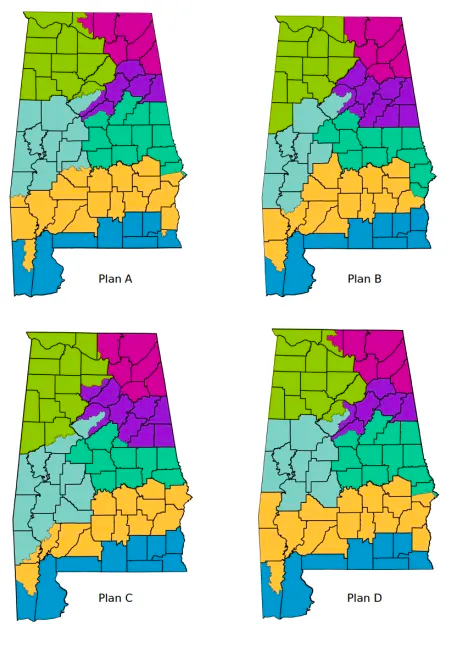

This is what it looks like when a group of voters is “cracked,” or split along district lines to ensure vote dilution, which is why this map got such horrid grades from gerrymandering watch dogs. Compare that to any of the four suggested maps from the plaintiffs in this case, and you can see the lines do a lot less dancing:

The frustrating aspect of this case is that it's hard to parse racial gerrymandering from partisan gerrymandering. Since Black voters predominantly vote with Democrats in Alabama, a map that dilutes the vote of Black voters can easily be described as a map that dilutes the votes of Democrats — which is not something Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is going to stop. On that question, I'm not going to pretend this case is simple.

If the court's decision is to revisit the precedent set by Gingles, and re-evaluate the tests set by the court in that case, we're opening up an entirely new can of worms. As it stands, I think Alabama has a strong argument that creating race-based sorting or racial targets for a district (i.e. ensuring district representations are proportional to race) is problematic. Given that the court already allowed these maps once, most court watchers imagine it will keep them in place – even if it’s on the narrow grounds of the plaintiffs being unable to produce alternative maps without prioritizing race. But I still think the inverse should also be true: Creating a district map that can clearly be linked to an attempt to dilute the vote of certain races, which this map can, should be illegal.

As this court has demonstrated, and many Americans across the political divide (including me) seem to agree, the Supreme Court is supposed to function by interpreting the laws written by Congress and the text of the Constitution. Last term, whether it was abortion rights not being explicitly laid out in the Constitution or the Environmental Protection Agency not having explicit authority in our energy sector, the court's majority argued in a wide range of cases to embody this ideal.

But look at what we have in this case: The Voting Rights Act says explicitly that any law is illegal which “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color." In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that Voting Rights Act plaintiffs must prove racist intent in order to prevail. But in 1982, Congress inserted the results-oriented language for the very purpose of overruling that decision, saying it did not matter whether a law was not motivated by racial bias but if it resulted in racial bias.

When it suits them, every American recognizes that gerrymandering is a form of voter obstruction, since it deprives groups of proper representation. With any luck, the court's ruling here will be a narrow one focusing on the inability of the plaintiffs to create a second predominantly Black district while only using certain race-neutral computer simulations.

What's unfortunate, irrespective of this case's particulars, is that such a map is allowed in the first place, and that the voters of Alabama are being forced to operate under such a map in this year's elections despite the fact the very panel created to adjudicate such gerrymandering struck the map down. Again: Gerrymandering does not just dilute the votes of Black people in the south — it damages voters of all stripes, including Republicans in places like New York City or California, effectively eliminating competitive congressional races.

This story is another anecdote that exposes the cracks in our democratic system — cracks that need to be sealed in order to restore voters' faith in how our representatives are elected.

Your questions, answered.

Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email and write in (it goes straight to my inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.

Across the developing world, China holds significant sway over the financial futures of many nations — while also facing the challenge of collecting debts it may never be paid. In a new article from The New York Times, Keith Bradsher examines how countries from South America to Africa to the Middle East turned to China as the lender of choice in the past decade. Now, with inflation ravaging many economies, China can decide whether to lend more, cut them off, or forgive small portions of the debt. Those debts, and China's attempts to help countries navigate them, collide with the United States' own financing of other nations’ development. The Times has the story.

Numbers.

- 80%. The percentage of Black Alabamians who are Democrats or lean Democrat.

- 9%. The percentage who have no lean.

- 11%. The percentage who are Republican or lean Republican.

- ~100. The number of consecutive days gas prices declined before starting to tick back up.

- $6.49. The price of a gallon of gasoline in Los Angeles on Monday, a record high.

- $3.86. The average price of a gallon of gasoline nationally.

- $3.77. The average price of a gallon of gasoline a month ago.

- 600,000. The number of so-called "dreamers" who will remain protected from deportation, despite a court's ruling that DACA is illegal.

Have a nice day.

Tim Lamont, a young scientist who is helping restore coral reefs, has made an incredible discovery: If he plays the sounds of healthy coral reefs back onto reefs being manually restored after damage, the reefs come back more quickly, and contain more species. Lamont is using the remarkable finding to accelerate restoration projects by recording sounds of healthy coral reefs and playing them in areas where reefs are in recovery. "Many of the noises had never been recorded before and the fish making these calls remain mysterious, despite the use of underwater speakers to try to 'talk' to some," BBC reports. You can listen to an interview with Lamont here.

❤️ Enjoy this newsletter?

💵 Drop some love in our tip jar.

📫 Forward this to a friend and let them know where they can subscribe (hint: it's here).

📣 Share Tangle on Twitter here, Facebook here, or LinkedIn here.

🎧 Rather listen? Check out our podcast here.

🛍 Love clothes, stickers and mugs? Go to our merch store!

Member comments