I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

Are you new here? Get free emails to your inbox daily. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today's read: 13 minutes.

New video!

My piece on the Zionist case for a ceasefire generated a lot of conversation and valuable dialogue, so we decided to publish it on YouTube as a video. It just went up this morning. If you missed our piece, please give this video a watch — or just click the video to support us by giving it a view, then press "subscribe" and keep tabs on our channel for the future!

Reader feedback.

There were lots of strong feelings about yesterday's edition on Chuck Schumer and Benjamin Netanyahu. A number of readers wrote to say that my bias was evident in “My take” and I am "too close" to the issue.

One reader said, "When do public comments from a senior US politician actually move from ‘speaking openly’ to meddling in foreign elections (or as Tulsi Gabbard would say, regime change politics)? Seems in this article, your personal bias about Netanyahu, and his policies, overshadowed your ability to sort this out. I imagine if the British Prime Minister lobbied for an election to topple Biden, our media would be out of their minds."

Quick hits.

- Hours after the Supreme Court cleared the way for enforcement of a strict new immigration law that allows Texas state police to arrest people on suspicion of illegally crossing the border, the law was blocked by a federal appeals court from taking effect. (The latest)

- Congressional leaders and the White House have reached an agreement on funding for the Department of Homeland Security, a major step toward finalizing a broader funding package. (The deal)

- Businessman Bernie Moreno, who was endorsed by former President Donald Trump, won his Senate primary in Ohio and will face Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown in November. Primary races were also held in Arizona, Florida, Illinois, and Kansas. (The results)

- Former President Donald Trump sued ABC for defamation after ABC host George Stephanopoulos said several times on air that Trump was "found liable for rape." (The lawsuit)

- Brazilian federal police have indicted former President Jair Bolsonaro on allegations of falsifying his Covid-19 vaccination data. (The indictment)

Today's topic.

The Supreme Court's social media case. On Monday, the Supreme Court seemed likely to side with the Biden administration in Murthy v. Missouri, a dispute between the administration and two Republican-led states (as well as five social media users) over how the federal government can combat misinformation on topics like Covid-19 or election fraud.

Back up: In 2021, the Biden administration was attempting to curb what it deemed misinformation about Covid-19 vaccines. In 2022, a group of Republican attorneys general representing private individuals and the states of Louisiana and Missouri sued the Biden administration, saying its actions had amounted to unconstitutional censorship. The group claimed the administration engaged in a pressure campaign aimed at social media companies in which it regularly flagged posts that it thought would contribute to vaccine hesitancy.

U.S. District Judge Terry Doughty ruled in favor of the states, ordering the Biden administration and top officials not to communicate with social media companies about certain content. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit then affirmed parts of that ruling but narrowed the agencies that could contact social media companies to the White House, the Surgeon General's office, the FBI, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). We covered that decision in September.

Now what? The White House appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, which suspended Doughty's ruling and agreed to hear the case. On Monday, a majority of justices seemed to side with the Biden administration.

While the Biden administration spent some time arguing the case should be thrown out because the states didn't have standing, much of oral arguments focused on the merits of the dispute and whether the Biden administration's contacts with social media companies actually violated the First Amendment rights of the challengers. Deputy U.S. Solicitor General Brian Fletcher, representing the Biden administration, argued that its actions amounted to a classic example of the bully pulpit, and officials were simply speaking their mind and calling on the public to act. He said the court of appeals "mistook persuasion for coercion."

Louisiana Solicitor General J. Benjamin Aguiñaga countered Fletcher, saying the government was badgering platforms constantly and with the implication of their leverage, like the possibility they could bring antitrust lawsuits against major social media companies that didn't cooperate. This badgering, which sometimes included verbal abuse and profanity, came with warnings "that the highest levels of the White House are concerned" about what the platforms were doing, and were "considering our options on what to do." Some of the platforms responded by changing their policies and practices.

Justices Elena Kagan and Brett Kavanaugh both referenced their own experience working in the federal government and expressed skepticism about Aguiñaga's position. Kavanaugh, who served in the George W. Bush administration, said government public relations officials "regularly call up the media and berate them," adding that a broad ruling against the Biden administration would mean that “traditional, everyday communications would suddenly be deemed problematic." Kagan quipped that she had "some experience with encouraging press to suppress their own speech" and said "this literally happens thousands of times a day in the federal government."

Justice Kentanji Brown Jackson asked Aguiñaga if there were a TikTok challenge where teenagers were jumping out of progressively higher windows, leading to injuries or death, could the government call platforms and say those posts are creating a public health emergency. Aguiñaga said the government could not, arguing that when "the government tries to use its ability as the government and its stature as the government to pressure them to take it down" it violates free speech.

While court observers noted a majority of the justices seemed to side with the Biden administration, Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas appeared open to letting the restrictions on government contacts with social media companies go into effect.

Today, we're going to examine some arguments from the left and right about these arguments, then my take.

What the left is saying.

- The left is hopeful the court will overturn the 5th Circuit decision.

- Some are heartened that some of the court’s conservative justices seem most skeptical of the plaintiffs’ argument.

- Others say the case should never have made it to the Supreme Court in the first place.

The Los Angeles Times editorial board said the “Supreme Court should affirm that government complaints are not free speech violations.”

The U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals’s reasoning, “if accepted by the Supreme Court, would prevent the government from suggesting that some material be taken down or limited in its dissemination because of concerns about public health or national security,” the board wrote. “The Supreme Court should resoundingly reject that approach and make it clear that the government violates free speech only when it uses its powers to coerce compliance.”

As Kavanaugh “suggested at oral arguments, such limitations on the government would forbid administrations from something they have done regularly even before the rise of the internet: expressing displeasure about particular stories to news outlets,” the board said. “A ruling against Louisiana and Missouri would make it clear that government officials may propose to social media companies that they remove or restrict certain information, so long as there is no coercion.”

In Vox, Ian Millhiser suggested “the Supreme Court’s center right appears increasingly frustrated with the judiciary’s far right.”

“These plaintiffs were able to identify several examples where government officials were curt, bossy, or otherwise rude to representatives from the social media companies when those companies refused to pull down content that the government asked them to remove. Notably, however, neither these plaintiffs nor the Fifth Circuit identified a single example where a government official threatened some kind of consequence if a platform did not comply with the government’s requests.

“Justices Elena Kagan and Kavanaugh seemed especially frustrated with the Fifth Circuit’s attempt to shut down communication between the government and the platforms, and for the same reason… both recoiled at the suggestion that the White House can’t try to persuade the media to change what it publishes,” Millhiser wrote. “For the time being, at least, most of the justices appear to recognize that the government needs to function. And that means that the Fifth Circuit’s attempt to cut off communications between the Biden administration and the platforms is likely to fail.”

In Just Security, Justin Hendrix and Ryan Goodman asked “how did Murthy v Missouri get this far?”

“There are important questions about the relationship between social media companies and the U.S. government, particularly when it comes to any governmental involvement in content moderation.” Hendrix and Goodman said. “While the legal questions presented are legitimate, a substantial amount of the underlying evidence now before the Court in this case is problematic or factually incorrect. Snippets of various communications between the government, social media executives, and other parties appear to be stitched together – nay, manufactured – more to support a culture war conspiracy theory than to create a credible factual record.”

“The plaintiffs may have succeeded in significant part no matter how the Supreme Court ultimately rules, though a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs would boost a broader political and socio-cultural strategy,” Hendrix and Goodman wrote. “In a contentious election year, there are signs this broader effort has succeeded in chilling coordination between platforms, government, civil society groups, and independent researchers on efforts to combat mis- and disinformation.”

What the right is saying.

- The right thinks the government clearly coerced social media companies to do its bidding.

- Some say a ruling for the plaintiffs would protect the First Amendment.

- Others push back on the idea that social media companies should be censoring inaccurate content at all.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote about the “government’s ‘thinly veiled’ social-media censorship.”

“The line between government coercion and attempts to persuade can blur, and the Supreme Court’s oral arguments on Monday in Murthy v. Missouri added little clarity. This is too bad because the government’s facile argument deserves a rebuttal,” the board said. “Government officials don’t threaten legal or regulatory retribution against newspapers, which they have little power to carry out. The same isn’t true for social-media platforms. White House officials issued thinly veiled threats of legal consequences if platforms didn’t do more to police so-called misinformation.”

“It’s hard to believe social-media executives would have been as obeisant without the government’s sword hanging over them. In private, White House officials also didn’t merely implore platforms to increase censorship. They demanded they do so and held regular meetings with executives when they pressed for updates,” the board wrote. “Injunctions by lower courts also may have been too broad. But none of this should stop Justices from making clear that government can’t use threats of punishment to coerce platforms to suppress speech.”

In The Daily Caller, Jenin Younes, one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs, argued “SCOTUS must protect the 1st Amendment.”

“Billed as an effort to protect Americans from ‘misinformation’ about a public health emergency, the record in this case reflects that the White House’s censorship operation spread its tendrils across public discourse on a wide variety of pandemic-related topics, including personal accounts of vaccine side-effects and provably true statements,” Younes said. “The Supreme Court has made clear that government cannot co-opt private companies to accomplish what it cannot directly.”

“As the Court has recognized, what is deemed false one day might the next be recognized to be true, so the notion that the government can effectively serve as gatekeeper of the truth is fundamentally flawed. But it is even more shocking when government officials acknowledge they are seeking to silence information that is or might be true,” Younes wrote. “This is the kind of heavy-handedness we should expect whenever the government disregards our civil liberties.”

In Hot Air, Jazz Shaw said the case “highlights the way that social media has evolved to become the modern version of the public square.”

“The courts are being forced to wrestle with the appropriate definition of ‘influence’ in such situations. The administration is quick to point out that the government has never been found to have imposed any sort of penalties or punishment on companies that declined to remove content that was deemed ‘controversial,’” Shaw wrote. “Of the many problems with this case, perhaps the largest is the fact that the social media companies are not technically capable of engaging in censorship.”

“Even if the plaintiffs prevail, the government has plenty of other ways of indirectly communicating its desires regarding such content to social media platforms,” Shaw said. “In reality, the platforms shouldn't be squelching any content except that which engages in or promotes crimes. This would be true of posts promoting physical violence, the abuse of children, the distribution of child pornography, offers to sell illegal drugs and other acts of a similar nature. Everything else you are likely to see online is simply a series of opinions of varying quality. It shouldn't be a crime to post your opinion even if you are wildly wrong.”

My take.

Reminder: "My take" is a section where I give myself space to share my own personal opinion. If you have feedback, criticism, or compliments, don't unsubscribe. Write in by replying to this email, or leave a comment.

- I still lean more towards the right on this one — government action that suppresses speech is alarming.

- The context during the pandemic, where there was some support for suppressing opinion, made it more important to defend free speech.

- Government speech is common, and their speech being persuasive is okay, but some instances crossed the line into coercion.

When we first covered this in September, I sided almost entirely with the right. My position didn’t change much after oral arguments.

In order to talk about what I think is most important here, I'm going to mostly ignore the "standing" question and focus on the merits of the case. It is worth noting that the justices seem split on whether Louisiana, Missouri and these social media users had standing to sue, and the case may start and stop there. But the merits are far more interesting and weighty to debate.

Fundamentally, the threat of government coercion and censorship feels more dangerous to me than the possibility of private platforms being left alone to make moderation decisions. I know Facebook and Twitter (now X) aren't exactly sympathetic figures here, but I'm imagining a world where Tangle becomes a global media empire, with dozens of writers across dozens of countries, soliciting interesting and provocative opinions to challenge people's ideas. And then I start getting emails from people at the White House telling me that they’d prefer it if I stopped what they define as misinformation, while the president opines on heavily regulating online newsletters that have accrued massive public influence. That would be deeply concerning.

It should go without saying that some of what the government’s contacts were doing was obviously helpful, like flagging accounts where people were impersonating the president’s family or sending over posts that amounted to terroristic threats. And of course, government officials did not write an email to Facebook executives saying “remove this post criticizing us or we’re going to regulate your company into oblivion.” They know doing that would be an obvious breach of their speech rights.

But is that really much different from what they actually did? If you are a Facebook executive reading emails from someone at the White House implying that the president is very concerned about what your platform is doing, considering regulatory action, and then making a request, how would you take it? In one instance, an official said "removing bad information" is "one of the easy, low-bar things you guys [can] do to make people like me think you're taking action."

That doesn’t mean all government communication is threatening or coercive. Of all the writing I came across on this, I thought Ilya Somin's take was the clearest and most to the point. As he points out:

The Free Speech Clause doesn't restrict any and all government efforts to constrain speech. Rather, it bars government actions ’abridging the freedom of speech.’ If the state—or anyone—persuades a private entity to cut back on speech voluntarily, the freedom of speech has not been abridged, even if the total amount of speech may be reduced.

In other words, there is a difference between the state convincing Facebook to remove a dangerous post and a state coercing Facebook into thinking the government may punish it if it doesn't. Government officials are perfectly within their rights to email a social media executive (or a news outlet) and say, "Hey, you are letting this post go viral, but here are 10 reasons we think it is spreading harmful information." They can persuade them that they should take action on certain posts. But they cannot coerce them. This, obviously, complicates things. A clever government official could easily make a threat without really making a threat.

Yet, the 5th Circuit found that the Biden administration did actually threaten to punish social media firms that did not comply, and I think they were right to find that. Here is how the 5th Circuit described the evidence:

The officials made inflammatory accusations, such as saying that the platforms were ‘poison[ing]’ the public, and ‘killing people.’ The platforms were told they needed to take greater responsibility and action. Then, they followed their statements with threats of ‘fundamental reforms’ like regulatory changes and increased enforcement actions that would ensure the platforms were ‘held accountable.’

That government employees talk to private sector employees all the time (as Kavanaugh and Kagan have said) is fine — but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a line they can’t cross.

Love him or hate him, Matt Taibbi generally has this story right. There is a "wide-scale partnership agreement between intelligence/enforcement agencies and media distributors," which is distinct from a PR person in the White House badgering a reporter for using a few quotes they don't like. The Biden administration had an entire operation dedicated to defining what qualified as misinformation and then trying to get social media companies to remove them, all while administration officials spoke publicly and privately about the possibility of taking regulatory action against those companies.

All of this, of course, comes with the hindsight that many of the posts were probably spurring debates worth having. Hindsight is 20/20, but I certainly do not think the posts questioning the origins of Covid-19 or the efficacy and safety of vaccines rose to a "public safety concern" the government needed to crush by coercing social media companies into doing their bidding.

It's also worth remembering where we were around this time. In January of 2022, one Rasmussen poll found that close to 50% of Democrats were willing to fine or imprison people who criticized vaccines. Over one in five Democrats supported temporarily removing unvaccinated parents’ custody of their children. That’s just one poll, from a well known right-leaning pollster, but those numbers are still terrifying. Attitudes like those were prevalent at the time — in the media and among government officials — and are part of why I'm so skeptical of efforts to "combat misinformation."

It is precisely in that environment where First Amendment speech protections are most important. Frankly, I was surprised there wasn't more pushback from Justices Alito, Thomas and Gorsuch, whom I expected to have a more forceful impact on oral arguments (I was also surprised there wasn’t more pushback from writers on the left).

In the end, it seems likely that the Supreme Court sides with the Biden administration and either narrows or throws out the 5th Circuit ruling. That’s fine, as I don’t think a sweeping injunction that prohibits government officials from contacting these companies is necessary or right (that would tilt the scales to violating the government’s speech rights).

However, my sincere hope if the Biden administration prevails is that the court finds a way to delineate between coercion and persuasion, and somehow limits the broad latitude the federal government has to influence online content moderation. The court’s ruling should narrow the ways the government can pressure these companies and make it clear that some of these actions are unconstitutionally coercive.

Disagree? That's okay. My opinion is just one of many. Write in and let us know why, and we'll consider publishing your feedback.

Help share Tangle.

I'm a firm believer that our politics would be a little bit better if everyone were reading balanced news that allows room for debate, disagreement, and multiple perspectives. If you can take 15 seconds to share Tangle with a few friends I'd really appreciate it — just click the button below and pick some people to email it to!

Your questions, answered.

Q: 2 of the 5 undecideds came from swing states. Why not all 5? It would have been interesting to see how the undecideds broke in the states where they play the key role.

— Ken from Lisbon, WI

Tangle: Great question, and actually a good opportunity to talk a little bit about our selection process for our new podcast series — The Undecideds — that we launched this week.

In our premier episode, which you can check out here, we introduced you to the five people we’re following, learned about their backgrounds, and got a sense for their political outlooks. We selected five people — Brian from Arizona, Diana from Florida, Clare from Ohio, Zahid from California, and Phil from Pennsylvania. Two of those states are considered swing states in the upcoming election (Arizona and Pennsylvania), but the other three aren’t.

We did consider just selecting people from swing states, but we ultimately decided against it for two big reasons: 1) Those states will be overrepresented in coverage already, and 2) States like Florida, Ohio and California still have very important down-ballot races every year, and Ohio and Florida have been known to swing presidential races, too.

Geographical diversity was also just one part of our calculus. We wanted demographic diversity, too. That means we have some diversity of representation by race, age, and gender. More importantly, we wanted diversity in thought. We have people who are religious and non-religious, people who never thought they’d consider Trump, people who are leaning away from Biden, people who are out of the political mainstream, people who closely follow the news, and people who are casting their first-ever presidential ballot.

Lastly, the most important criteria of all was to select people who have the courage to be honest about their backgrounds, misgivings, and thought processes. We narrowed down the massive response we got from readers to about three dozen people we reached out to personally, narrowed that group down to about 15 we thought could be really compelling interviewees, and then made our final decision to try to get those demographic, ideological, and geographic diversity of representation.

We’re really happy with how that turned out. So if you still haven’t yet, please check out the first episode of The Undecideds.

Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to my inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.

Schools across the U.S. and Europe are beginning to lock up students' phones during class — or ban their presence at schools outright. School districts in at least 41 states have bought magnetic pouches that allow them to seal the phones off from students without turning them off or confiscating them. “The results for us were just a game-changer,” Patricia Shipe, president of the Akron Education Association, said after her district began using them. Phone bans aren't new in school, but bans are becoming increasingly common as risks about screen time and social media become better understood. Vox breaks down the debate.

Numbers.

- 39%. The percentage of Americans who said the U.S. government should take steps to restrict false information online, even if it limits freedom of expression, according to a 2018 Pew Research poll.

- 55%. The percentage of Americans who said the U.S. government should take steps to restrict false information online in a 2023 Pew poll.

- 56%. The percentage of Americans who said tech companies should take steps to restrict false information online in 2018.

- 65%. The percentage of Americans who said tech companies should take steps to restrict false information online in 2023.

- 75%. The percentage of Americans who said they don’t trust social media companies to make fair decisions about what information is allowed to be posted on their platforms, according to a 2021 survey from Cato/YouGov.

- 58%. The percentage of Americans who said social media sites should use the First Amendment as the standard for their content moderation decisions.

The extras.

- One year ago today we wrote about Donald Trump’s imminent hush money indictment.

- The most clicked link in yesterday’s newsletter was the survey about tipping.

- Nothing to do with politics: A man in Montreal received a letter informing him that he was legally dead.

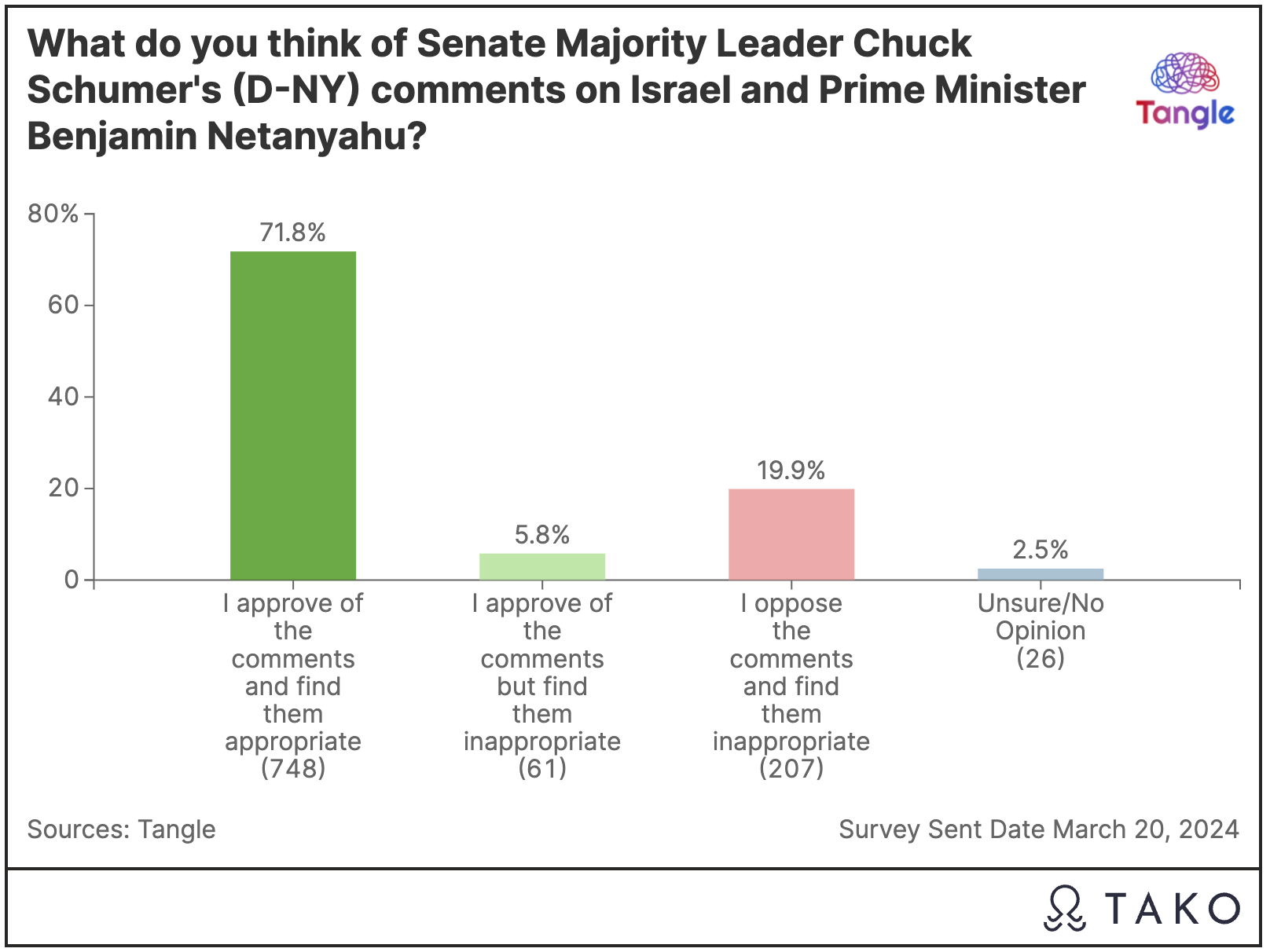

Yesterday’s poll: 1,050 readers took our poll on Schumer’s comments about Netanyahu with 72% approving and finding them appropriate. “It’s inappropriate to accuse Schumer of ‘interfering’ with a foreign ally when we fund a not insignificant portion of their Defense. The US providing that funding is also a form of ‘interference,’” one respondent said. Due to an error in the poll, we did not have a response category for people who opposed Schumer’s comments but found them to be appropriate.

What do you think of the communication between White House officials and social media companies? Let us know!

Have a nice day.

Paul Myers, who lives in York, England, suffered a cardiac arrest at a McDonald’s on his way to Sunday services. Thinking quickly, one patron performed CPR long enough for another unlikely hero to step in. An employee trained in using the defibrillator used his knowledge to save Paul’s life. From there, he was taken by helicopter to a hospital where he recovered. Mr. Myers expressed his gratitude to everyone, especially the McDonald’s employee. "He didn't want to take any glory and that really impressed me because what he did, and what the other man did, those first few moments are really key and, without that, I probably wouldn't be speaking to you today," Myers said. The BBC has the story.

Don't forget...

📣 Share Tangle on Twitter here, Facebook here, or LinkedIn here.

🎥 Follow us on Instagram here or subscribe to our YouTube channel here

💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar.

🎉 Want to reach 97,000+ people? Fill out this form to advertise with us.

📫 Forward this to a friend and tell them to subscribe (hint: it's here).

🛍 Love clothes, stickers and mugs? Go to our merch store!