I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, ad-free, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

First time reading? Sign up here. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today's read: 12 minutes.

We're covering the situation in Kazakhstan. Plus, I answer a reader question about what I think we should do with criminals (if I think prison is bad).

Quick hits.

- The White House announced it was giving $308 million of additional aid to Afghanistan, bringing total U.S. aid for the impoverished country and Afghan refugees in the region to nearly $782 million since October. (The donation)

- Richard Clarida, the Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve, resigned yesterday amid scrutiny over financial transactions he made at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. (The resignation)

- President Biden said yesterday that private health insurance companies will need to reimburse the cost of at-home Covid-19 tests beginning on Saturday. As many as eight per month can be reimbursed. (The rules)

- Biden will also announce his support for a "filibuster carveout" in Atlanta today in order to promote Democrats' national voting rights legislation by a simple majority vote. (The move)

- House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA) have both said they are considering a push for legislation that bans lawmakers from trading certain stocks. (McCarthy) (Ossoff)

Today's topic.

Kazakhstan. If you've been reading the news recently, you have probably stumbled across some stories about Kazakhstan. The country is currently in the midst of civil unrest that has left at least 164 people dead, and more than 5,800 civilians detained.

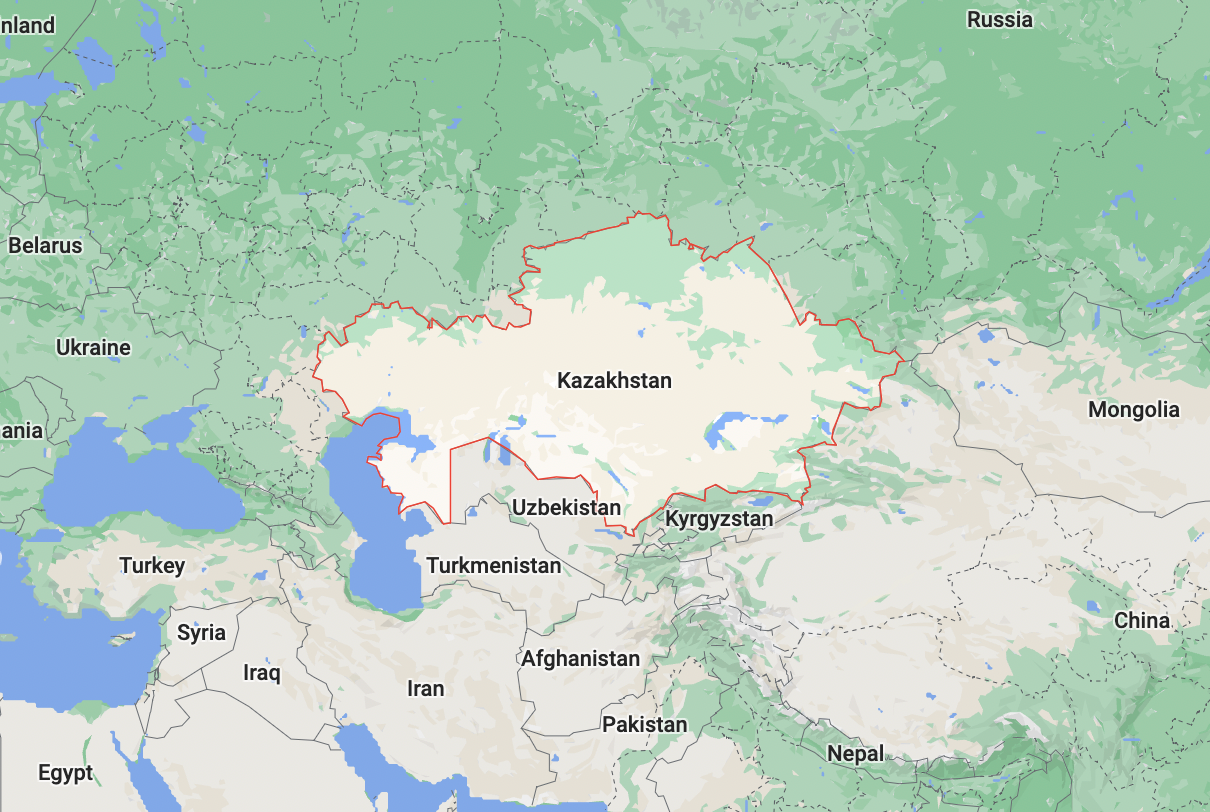

Some background: Kazakhstan is a large country that sits in Central Asia, and borders both Russia and China. It’s in an arid, mountainous region, and despite its size just 19 million people live there (it's about as big as Western Europe, which has a population of 196 million).

Kazakhstan had been part of the Soviet Union but gained independence in 1991 after the Soviet Union's collapse. Despite having some of the largest uranium and oil reserves in the world, and producing some 1.6 million barrels of oil a day (about 2% of the world's crude oil), the average income of citizens there is about $2,800 a year. Still, that number is a tad bit misleading: Incomes tend to be higher in the cities while many live in poverty in the rural areas of the country. The poverty rate in Kazakhstan has also fallen substantially over the last 20 years.

Who runs Kazakhstan? From 1990 to 2019, Kazakhstan was run by Nursultan Nazarbayev, who had strong ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin and was a member of the Communist Party. Nazarbayev focused most of his time as president on economic reforms and never embraced democracy. In 2019, he resigned as president to give way to Kazakhstan's current president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. Then Tokayev brought Nazarbayev on to lead his security council.

And what just happened? A few weeks ago, Tokayev announced that he was lifting the price cap on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Kazakhs had bought cars that run on LPG because it is cheaper than other kinds of fuel, so the removal of a price cap — in oil rich Kazakhstan — was met with fury. The price of LPG doubled almost immediately.

Protests are illegal in Kazakhstan without a government permit. Previous demonstrations have been dealt with harshly, according to the BBC, and this one was no different. Russian peacekeeping troops were sent in under the authority of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and some 2,500 soldiers were deployed. It's the first time the CSTO has been used in this manner.

Why is the unrest so acute? Philip M. Nichols, a member of UPenn's Russia and East European Studies program, laid out three reasons:

1) Protesting is in the fabric of Kazakhstan, and many of its citizens have repeatedly hit the streets over economic issues, land sales or other grievances in the last 30 years.

2) Despite being fabulously wealthy, supplying nearly half of the world's uranium and a chunk of its oil, Kazakhstan’s wealth is highly concentrated and most Kazakhs don't benefit from the sale of natural resources.

3) The economic disruption caused by the lifting of the LPG price controls.

Now what? Once protesters hit the streets, it became clear this was about more than just fuel prices. As Nichols put it, there is an underlying dissatisfaction being acted on. Some tried to tear down statues of Nazarbayev, who has kept a powerful position in government despite resigning. Tokayev responded to the protests by removing Nazarbayev and other top government officials from their posts. He also reinstated the cap on LPG prices. But that has not satisfied protesters.

The country has also spent much of the week sealed off from the outside world. Its largest airports are closed or have been taken over by the Russian troops who are part of CSTO. Phone lines and internet services were down, so information coming out of the country has been hard to come by.

It's unclear exactly how the situation there might impact the world at large. Tokayev has declared that foreign agents helped prompt the opposition protests, and given the strong relationship the U.S. currently has with Kazakhstan, that means our supporting those protesters could cause problems.

This, obviously, is not a traditional issue to run through the American lens. I struggled to find any opinion pieces in English from Kazakh natives. So below, we're just going to share some excerpts from opinion pieces about what’s happening in Kazakhstan that I think add valuable insight.

Some opinions.

In The Washington Post, Josh Rogin said "the West should use Putin’s new problem to dissuade him from recklessly starting another crisis in Ukraine."

"To be sure, Putin has long preached about reasserting Russian control over all the former Soviet territories, including Kazakhstan," Rogin wrote. "Putin has said the country was artificially invented by former prime minister and president Nursultan Nazarbayev, who founded and ruled it for more than three decades as a thinly veiled dictatorship, mimicking Putin’s own model. Though still pulling strings behind the scenes, the now-81-year-old Nazarbayev has clearly lost control of the situation, forcing him to run to Putin for emergency help.

"For the first time, the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) has deployed troops inside Kazakhstan, supposedly at Kazakhstan’s request, to fight regular citizens the government now calls 'terrorists,'" they said. "It’s still early, and much is unknown, but there’s a real risk that the Kazakhstan crisis could turn into a quagmire Russia wasn’t planning for."

Ed Morrissey wrote that Putin is not a fan of popular uprisings.

"While the US and NATO negotiate to de-escalate the war in Ukraine, Russian troops landed in Kazakhstan overnight to put down a popular uprising against the Moscow-friendly government," Morrissey said. "Putin ordered it under a collective security agreement with several of the former Soviet republics on Russia’s border, but the question will be whether they ever leave...

"Russian troops now occupy Crimea and parts of the Donbass, a situation that has been ongoing for eight years now," he said. "In 2008, Putin sent troops into Georgia and forcefully severed its Abkhazia and South Ossetia provinces. Putin also made it clear that he would use his military might in Belarus if necessary to keep Putin’s toady Alexander Lukashenko in power in the face of a popular uprising there."

The Bloomberg editorial board said "ordinary Kazakhs have plenty reason of their own to be angry," and Tokayev would be "better off addressing that frustration than trying to violently suppress it."

"A host of wider grievances helped the unrest spread quickly: Rising inflation has eaten into pocketbooks and deepened already stark inequality," the board said. "A wealthy elite is seen as siphoning off much of the country’s oil and mineral wealth. State services have languished, even as citizens have been allowed little say in their own governance.

"Tens of thousands of people took to the streets, overrunning government buildings, police stations and the airport in Almaty; by Friday, when Tokayev claimed order had largely been restored, more than three dozen protesters and police had been reported killed," the board said. "Crowds directed their ire in particular at Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled Kazakhstan for three decades before installing Tokayev as his successor in 2019. Even after stepping down, Nazarbayev continued to wield influence as the head of the country’s security council, while his family members grew rich through stakes in critical businesses."

In The Wall Street Journal, John Bolton said the West needs to "be firm" with Putin as he seeks to expand his control.

"Doubtless, Moscow finds it unhelpful to have a bordering autocracy thrown into turmoil, but the West is badly mistaken and potentially at risk not to see the opportunities presented to Mr. Putin," Bolton said. "His strategy to re-establish Russian hegemony within the borders of the former U.S.S.R. has been both patient and agile, and Kazakhstan’s troubles afford him significant possibilities.

"This first CSTO deployment into a member country contravenes its charter, which refers only to defending against external aggression," Bolton wrote. "The initial 2,500-man force is nearly all Russian, and Mr. Tokayev has given orders to 'shoot to kill without warning.' Other Russian operations, in Moldova and Nagorno-Karabakh (the territory central to the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict), are also poorly disguised Russian expeditionary forces, helping Moscow sustain conflicts throughout the former Soviet Union. This prevents countries from reducing Kremlin influence, hampers potential Western investment because of increased political risk, and quite possibly facilitates the reintegration of the independent states into Russia’s empire."

In DW, Andrey Gurkov said the unrest will deter Moscow's aggression.

"A Russian military operation on Ukrainian territory has now become less likely," Gurkov wrote. "There are two reasons for this. One is that a Russian military intervention could lead to domestic instability inside Russia similar to the unrest unfolding in Kazakhstan. The other stems from the fact that Russia must now dedicate much more attention to its southern neighbor, Kazakhstan.

"Until now, Kazakhstan was considered a largely stable country with a dependable government," Gurkov said. "The fact that thousands of frustrated Kazakhs are now venting their anger should be a warning to the Kremlin. It should compel Russia to consider the domestic implications of a threatened or alleged military operation with which it is currently trying to intimidate the US and NATO. So far, Russia only seems to have weighed up what impact such a move would have on its foreign policy and trade. Given the crisis in Kazakhstan, however, Russia may now also have growing doubts over whether its population would back it."

The Guardian's editorial board warned of "danger ahead."

"The west has limited influence, but is not without leverage," the board said. "Large sums of Kazakh money are sequestered in London (where 'British professional service providers enable post-Soviet elites to launder their money and reputations', a stinging Chatham House report noted last month). Anti-corruption campaigners have rightly urged that as the rich and well-connected flee, law enforcement agencies, financial institutions and service providers should be watching carefully and reporting, freezing and seizing assets as appropriate. The US, EU and UK should also do their utmost to urge the leadership to respect protesters’ rights."

My take.

Obviously, the intricacies of the situation in Kazakhstan are not in my area of expertise (though I'm certain there is a Tangle reader typing away already — I'm ready for you!).

One of the insightful excerpts I really loved while researching this piece came from Penn's Philip M. Nichols. He said this about the protesters:

"Kazakhstani people are pretty much like people here, and the things that go on here are the things that go on there. We don’t want to look at what’s going on there and say, ‘Oh, we can make this simple: It’s a bunch of ex-nomads who are pissed off about having to pay more for car fuel and are mad at their dictator government.’ This situation is as complicated as the issues that we have going on here. We need to think about it in the same way, that there isn’t a simple explanation nor is there a simple solution, and these people are not one-issue caricatures. They’re complicated people with complicated lives in a fulsome system. They’re just like us, and they’re really, really brave. It’s very cold in Kazakhstan right now, and they’re out there every day, with special forces shooting at them. You’ve got to admire that kind of courage."

What I can say, having followed so much of Russian and global politics, is that Kazakhstan has long been considered one of the most stable of the Central Asian countries that rose out of the Soviet Union's collapse. Despite its history of civil unrest, and the culture of protest that has helped shape the country's destiny, reading about hundreds of people being killed and thousands more jailed in street protests is a truly horrifying turn of events.

Frightening, too, is this first use of the CSTO in a domestic military action, one that could soon be replicated in other former Soviet countries in the region.

It seems the punditry is largely divided on whether these developments will deter or embolden Putin. On one hand, it's a reminder of how disruptive a civilian revolt can be — one that often feels on the precipice of occurring even in Russia, where dissatisfaction has been high. On the other hand, Russian troop presence in Kazakhstan may not be temporary, only adding to the long reach Putin has in the region — which now extends across Central Asia.

It'd be nothing more than an educated guess to say what is going to happen — but it's a situation worth watching for the rest of the world, even though it may feel distant and irrelevant right now.

Have thoughts about "my take?" You can reply to this email and write in or leave a comment if you're a subscriber.

Your questions, answered.

Q: So if you don't like putting people who break the law into prison, what do you want to do them? Are you one of those use 'social service workers' vs police and prisons?

— Te, Mesquite, NV

Tangle: It's important not to conflate issues here. The question of who should respond to 911 calls (armed police, social service workers, both, or somewhere in between) is very different from what to do with people who have already committed crimes. I have a lot of thoughts about both, but in yesterday's reader question I was referring to the latter: What to do with people who commit crimes.

To start with, you need to work from my baseline, which is that prisons may work as retribution (if our model is an eye for an eye) but they do not work as a means of rehabilitation. There are a million different ways to make this point, but the most obvious is that two out of three former U.S. prisoners are rearrested within three years and 77% are rearrested within five years. This is known as the "recidivism rate," the rate at which released prisoners are rearrested, and it is startlingly high in the U.S. (in Norway, the recidivism rate is just 20%).

To simplify this point further: If your son is cursing regularly, and every time he curses you take away his phone as punishment, and then 8 out of 10 times he gets his phone back he starts cursing again within five days, you'll likely conclude your punishment is not working. Yet, somehow, we have not been able to come to that conclusion about prisons, despite the fact that instead of taking a phone away we are separating people from their families, destroying most opportunities they'll ever have at getting a future job, and sometimes subjecting them to abject torture.

Given the baseline that our prisons are dysfunctional, inhumane, inefficient, short-staffed and also do not deter people from committing more crime, there are two fundamental options when it comes to this question: Do we want to reform the prisons we have? Or do we want to just use them a lot less? Or both?

Reformation would likely mean tearing down and rebuilding many of the jails and prisons we have now and moving to a system more like Norway's, where inmates are better treated and prepared to re-enter society when they finish their term, and are less inclined to commit crimes than when they entered. That is what success looks like.

Using prisons less would mean not having 1.8 million people incarcerated at a time, the highest incarceration rate in the world, as we did at the end of 2020. If all our prisons were made a city, it'd be the fifth most populous city in America, behind New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston. If you think this is a "working" prison system I'm not really sure what to say. With rare exceptions (Bernie Madoff comes to mind), I don't think non-violent criminals should be in jail at all. If we're going to imprison violent criminals, which is a rational thing to do, we should put them in prisons that make them less violent, not more violent. Right now, we are doing the opposite of that.

Obviously, this is not a simple issue. But my point yesterday — and the radical view of mine I was alluding to — is that it is crystal clear to me that our prison systems are not working. They are the opposite of working. They're actively making our country a worse place to live for millions of people, preying on the poor, destroying livelihoods and families, and not even coming remotely close to what they are supposed to be doing (deterring crime and thus keeping us all safer). Thus, I think it's pretty reasonable to believe that we should change what we're doing.

Want to ask a question? You can reply to this email and write in (it goes straight to my inbox) or fill out this form.

A story that matters.

With Covid-19 spreading rapidly due to the Omicron variant, one metric many epidemiologists and Americans have been keeping an eye on is the number of hospitalizations. Yesterday, the U.S. hit a grim milestone: Tuesday’s total of 145,982 people in U.S. hospitals with Covid-19 broke the previous record from January of 2021. "Colorado, Oregon, Louisiana, Maryland and Virginia have declared public health emergencies or authorized crisis standards of care, which allow hospitals and ambulances to restrict treatment when they cannot meet demand," The Washington Post reports. The good news? There are still fewer people in the ICU than at the peak of the pandemic. Omicron still appears to be less severe and cause fewer deaths. And many of the Covid-positive cases are people who went to the hospital to treat another ailment, but tested positive for asymptomatic Covid upon arrival.

Numbers.

- 20.2%. The percentage of Kazakhstani people who are ethnic Russians, as of 2017.

- 70.2%. The percentage of Kazakhstani people who are Muslim, as of 2009.

- 42.6%. The percentage of Kazakhs who live in a rural part of the country.

- 40%. The percentage of the world's Uranium output that comes from Kazakhstan.

- Five. The number of countries that border Kazakhstan: Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and China.

Have a nice day.

The James Webb Space Telescope has just begun its flight, and it’s already sending home good news: It's full of fuel. One of the unknowns on the launch was how much fuel would be used early on, which is dependent on how accurately the telescope was shot into orbit and then into space. "Right now, because of the efficiency or the accuracy with which Ariane 5 put us on orbit, and our accuracy and effectiveness implementing our mid-course corrections, we have quite a bit of fuel margin right now relative to 10 years," Bill Ochs, the Webb project manager, said, speaking of an earlier fuel estimate. They now estimate the telescope has fuel for 20 years of use. The telescope is expected to perch one million miles from earth before settling in and observing the distant galaxies. Space.com has the update.

❤️ Enjoy this newsletter?

📫 Forward this to a friend and let them know where they can subscribe (hint: it's here).

💵 Drop some love in our tip jar.

🎧 Rather listen? Check out our podcast here.

🛍 Love clothes, stickers and mugs? Go to our merch store!

🙏 Not subscribed? Take the next step and become a subscriber here.

Member comments