I'm Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, ad-free, non-partisan politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum — then my take. First time reading? Sign up here. Rather listen? Check out our podcast.

Today's read: 12 minutes.

We're covering the new global corporate tax minimum and what it means. Plus, a reader question about the United States Postal Service.

Correction.

In yesterday's newsletter, a few sharp-eyed readers pointed out that we used the expression "Taiwan's air space", while some of the columnists we cited referred to the ADIZ (air defense identification zone) instead. There is an important distinction we did not point out and made a mistake on: Taiwan's airspace is sovereign territory that extends about 12 nautical miles off the coast of the island. The ADIZ is a designation for airspace that extends much further out and requires a specific positive identification from any aircraft to cross into.

In recent weeks, China has been entering Taiwan's ADIZ, not its sovereign air space, which would be a much more grave engagement and mean they were far closer to Taiwan's coast and capital, Taipei City. It's a simple mistake but a very important distinction, and we appreciate the readers who pointed it out!

This is the 43rd Tangle correction in its 114-week history, and the first correction since August 24th. I track corrections and place them at the top of the newsletter in an effort to maximize transparency with readers.

Big story tomorrow...

In tomorrow's subscribers-only edition, I am writing about the attempted CIA assassination of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, recently reported on in Yahoo News. I'll be talking with Assange's lawyer today in an exclusive interview, and then explaining the latest about what we know in tomorrow's newsletter.

Remember: If you're not yet a subscriber, it's easy to become one: Just click here.

If you are a subscriber: We have new membership tiers you should know about, including a "Thank you" tier to support our podcast and original work. You can upgrade to that membership by clicking here.

Quick hits.

- President Biden announced a series of measures in an attempt to address the supply chain bottleneck, including opening the Los Angeles port 24 hours a day, seven days a week. (The plan)

- At least five people were killed and dozens injured in Beirut during a Hezbollah-led protest calling for the removal of the judge investigating the devastating explosion at its port last year. (The story)

- Former President Barack Obama will campaign with Terry McAuliffe in the Virginia governor's race. (The race)

- The House committee investigating the Jan. 6 Capitol riot issued a subpoena to Jeffrey Clark, a former Justice Department official under President Donald Trump. (The subpoena)

- The FDA released new voluntary guidelines to reduce the amount of sodium in commercial food products. (The salt)

Today's topic.

The new global minimum corporate tax. Over the weekend, 136 nations officially agreed to enforce a corporate tax rate of at least 15 percent, and also pledged to institute better systems of taxing profits fairly, where they are earned. The agreement, announced by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), included countries like Ireland that once opposed the deal but now support it. The overarching goal is to address multinational companies that have made a habit out of rerouting their profits through low tax rate countries. The OECD has been leading talks on a plan to institute a minimum rate for a decade.

Explain it: When a major company (like Apple) is trying to decide where to set up shop, or where to file its profits, it often hunts for the country with the most favorable tax rules. Because being able to tax a company like Apple brings in a lot of revenue, nations have strong incentives to lower their tax rates in order to win Apple's business. If you're collecting a 10 percent tax on Apple's profits, that might be better than collecting 0 percent tax on Apple's profits and 15% on everyone else's. This has left smaller and/or poorer countries in what some economists call a "race to the bottom" to attract multinational corporations.

The new rules: There are two main threads to the new rules. One is a tax rate minimum that will apply to companies with annual revenue of more than $750 million. If approved (formally) this week at the G20 summit, it will generate about $150 billion in additional global tax revenue per year. The other is an overhaul of tax rules that will divide company tax revenues in a way that favors countries where the customers of that company are based. It will also reallocate taxing rights on big companies above a certain profit threshold. The new rules will go into effect in 2023.

Who signed it? Just about everyone, except Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. That's because some developing nations oppose the rule. They say having a lower corporate tax rate is a good way to attract investment, and since none of them can go lower than 15 percent now it will benefit countries that are already ahead. Ireland, which used its 12.5 percent tax rate to attract major foreign investment (including Apple, which has a home base there), agreed to the deal after securing a compromise on the wording of the agreement. It had previously called for "at least" a 15 percent global minimum tax, but the words "at least" were removed.

The reforms had been agreed to in principle at the G7 meeting in London this past June. But the latest announcement marks the official agreement, which is expected to be finalized this week at the G20 summit. Below, we'll take a look at some reactions from the right and left, then my take.

What the left is saying.

The left supports the agreement, though they think it could have gone further.

In June, when this deal was first proposed, The Guardian's editorial board said it was "genuine progress."

“International corporate tax rules were designed a hundred years ago, to protect multinational companies from predatory governments and the threat of double taxation,” the board said. “But since the late 20th century, and particularly in the digital era, the power relationship has been inverted. In the age of high globalisation, multinational giants played pick and mix with tax jurisdictions, salted away profits offshore through baroque ownership structures, and used their power to play countries off against each other.

“A minimum global corporation tax of at least 15%, as proposed, would establish a floor on what the US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen has described as ‘a 30-year race to the bottom on corporate tax rates.’ It would also lead to real pressure on the world’s tax havens – many of them overseas territories of the United Kingdom – to follow suit,” the board concluded. “The second part of the deal is intended to reform the tax framework to more fairly reflect where companies such as Amazon, Google and Facebook do business and make their money, as well as where they are headquartered. This is also overdue. The economic realities of the digital age mean that the tech titans have been getting away with paying far too little for far too long.”

In The New York Times, Peter Coy asked if "the race to the bottom" was over.

“One argument against a global minimum tax is that it’s a way for rich countries to gang up on companies and extract excessive taxes to finance their costly welfare states,” Coy said. “That’s what some conservatives contend. Another argument against a global minimum is that it could harm poor countries with low tax rates. A poor nation that’s unattractive to multinationals might want to set its corporate tax rate very low to attract investment, and the global minimum prevents it from doing that. But [Professor Daniel] Drezner says that in practice, many of the countries with very low or zero corporate taxes aren’t poor nations but comfortable tax havens, like Jersey, Guernsey, Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands.

“In June, as the deal was taking shape, the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business asked top American and European economists what they thought of it. A majority on both continents thought it would 'limit the benefits to companies of shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions' without distorting their investment choices in economically inefficient ways. Smaller majorities had confidence that it was achievable. That part remains to be seen — it’s one thing to ink a deal, but quite another to enforce it. One of the economists surveyed... told me by email that in an ideal world each country would set a corporate tax rate based on its 'needs, preferences or constraints.' But, he wrote, 'that first-best may not be attainable at all, or may be subjected to gaming, so setting a global minimum is a way (albeit a second-best way) to limit the ‘race-to-the-bottom.’ Sometimes the second best is the best we can hope for."

In Bloomberg, David Fickling was skeptical anything would change.

"So much money now moves through the world’s offshore financial centers that such paper transactions now account for a greater flow of capital than any country receives from genuine foreign investments," he wrote. "Far from taking a larger share, most developed nations have coped with the leakage of taxable profits over the past decade by cutting their own corporate tax rates — a tacit admission that enforcement has failed. Mandatory disclosure rules introduced in 2014 to prevent European banks’ use of tax havens seem to have made no real difference, according to a report last month by the EU Tax Observatory. Why have all these worthy efforts achieved so little? One explanation suggested by the list of powerful figures named in the latest leaks, dubbed the Pandora Papers, is simply that the people in charge of writing the laws and treaties that underpin international capital flows have much to gain from the current set-up.

"Any attempts to restrain them are like a game of Whac-A-Mole," he wrote. "That applies even to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s attempts to reset the world’s tax rules via an accord between 130 jurisdictions due to be finalized this month. The centerpiece of the proposal, a 15% global minimum tax rate that can be applied unilaterally by governments that feel they’re losing out, is over time as likely to end up as a global maximum tax. The Biden administration’s attempts to restore rates cut to 21% under Donald Trump will stop at 26%, rather than the 28% originally sought or the 35% that existed previously. There’s little sign the race to the bottom that’s been going on for four decades is about to end."

What the right is saying.

The right is generally opposed to the changes, saying they will hurt the United States in the end.

In June, when this was first proposed, Mick Mulvaney said Americans should "root" for the Irish fighting higher corporate taxes.

"The premise behind the minimum global corporate tax is simple: Most governments around the world are looking to raise money," Mulvaney said. "But they don’t like taxing the middle class, as this tends to result in lost elections, and there aren’t enough rich people to soak to raise the necessary funds. That means that governments have started to look to corporations as piggy banks they can raid. The Microsofts and Apples of the world don’t garner much public sympathy when it comes to paying their 'fair share.'

"In the not-so-distant past, the U.S. knew better," he wrote. "We knew that low corporate tax rates boosted investment, productivity, jobs and wages—all of which encouraged a prosperous economy. When the U.S. cut the corporate rate to 35% under Ronald Reagan —giving us the lowest rate in the world—we reaped huge benefits at the expense of other countries with higher rates. But those countries also learned from our example. They even started beating us at our own game, which led to an exodus of U.S. business to more-favorable tax climes, including Ireland. By the time we lowered rates under President Trump, that 35% U.S. corporate tax rate had become the third highest in the world... Competition among nations, or states, on tax rates is just that: competition. And if you are losing a competition, there are two ways you can respond. One is to get better. The other is to prevent the competition from happening."

The Wall Street Journal editorial board said this is a "gambit" to impose much steeper taxes domestically.

"Other governments locked in the lowest minimum-tax rate they could, and then tried to delay full implementation as long as possible," the board said. "Ireland is a case in point... it insisted that rate be a cap rather than a floor. The OECD proposals over the summer spoke of a rate of ‘at least 15%’ and, at Ireland’s (and Switzerland’s) behest, that ‘at least’ is now gone...The message from all this to Congress is that the rest of the world will not easily allow a global minimum-tax rate to drift upward to match an uncompetitive U.S. rate, no matter what [Treasury Secretary Janet] Yellen hopes.

"Ms. Yellen and progressives hope the OECD global-tax gambit will provide political cover to impose much steeper taxes in the U.S. Now Capitol Hill is on notice: There is a limit to how much other governments will hobble their companies with higher taxes," they wrote. "Democrats want to raise taxes in the U.S. now, while foreign tax increases are years away. The global tax project is bad policy that will reduce tax competition that has helped countries like Ireland attract more investment and grow faster. It serves the interests of the political class, not working people. But Congress shouldn’t compound the damage by making U.S. taxes even more burdensome than Ms. Yellen’s misguided global tax does.”

The National Review editorial board criticized the "race to the bottom" argument.

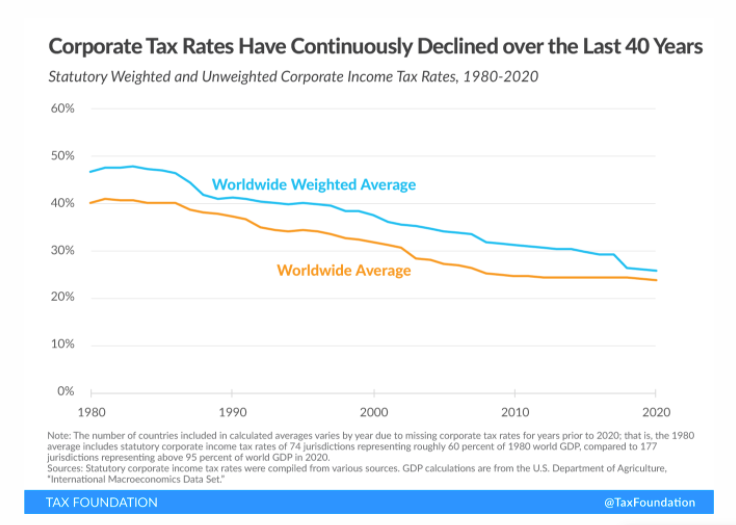

"The problem with that argument is that it hasn’t happened," they wrote. "What has been derided as a race to the bottom in reality has been more of a slow glide to the middle. Over the past 40 years, corporate tax rates have slowly declined across the board, and the worldwide average in the past ten years has settled right around 25 percent. The distribution has also become less variable over that span: The most common statutory rates globally are between 20 and 25 percent. The United States used to be far above the global average. The federal statutory corporate-tax rate was 35 percent until the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced it to 21 percent, where it currently stands.

"The domestic political agenda behind Biden and Yellen’s global antics is obvious," they wrote. "Democrats want to raise the federal corporate rate back above the global average again, to 26.5 percent. Since states also levy corporate taxes, the average corporate-tax rate for the U.S. would be 30.9 percent, which would be third-highest in the OECD, trailing only Colombia and Portugal... Large, powerful countries shouldn’t force smaller, weaker countries to adopt tax policies that facilitate the large countries’ extraction of revenue from corporations. In any other context, the Left would cry, 'Imperialism!' but apparently tolerance of global differences must be set aside if it gets in the way of revenue. Setting tax policy is an inherent power of governments, and it should be left to them, not outsourced by international agreement."

My take.

I'm genuinely torn.

The argument that each nation should have the freedom to impose its own tax rates resonates with me, but I'm also not sure this deal violates that principle. After all, this is a global agreement where all 136 nations are opting into the 15% minimum, so it's not as if they are being forced (clearly, evidenced by the countries who refused to sign on, it's possible to say no). It seems obvious that developing nations who are struggling to woo new investors are going to be hurt the most by a global tax minimum, and I haven't exactly seen any arguments spelling out why that won't be the case (though I'm open to them).

At the same time, I'm not sure classifying this as a "race to the middle" is accurate either, as the National Review board does. They cite the Tax Foundation's numbers, claiming rates have "slowly declined" and "settled" in the middle. But if you look at the graph they link to, I'm not sure I'd describe it in either of those ways. I'd say the rates have precipitously declined by 15% from where they used to be. Here is what it looks like:

It's also true that a lot of the initial fear-mongering about this tax hasn't come true. For instance, one of the grave warnings this summer when the deal was being negotiated was that the global minimum tax was going to disrupt the stock market, because multinational corporations were going to take such a hit. David Fickling, in an article over the summer, examined that claim and basically put it to bed.

Larger questions still need to be answered, though. The most obvious is how and whether countries will actually enforce these minimums, or if new loopholes will simply be created and exploited. So many caveats and carve outs have already been put into this deal, it's hard not to imagine the latter. It's also true that, for Biden and Yellen, these changes are almost certainly tied to a domestic agenda to raise corporate taxes — and perhaps even to create a uniform baseline for state taxes, too. Remember: Some nine U.S. states have no income tax, for instance, so one might wonder why the same global logic wouldn't apply inwardly, as Mulvaney argued.

Of course, there's something about the spirit of the pact that I support. We want obscenely profitable, giant companies paying their fair share of taxes and we want them doing it in the countries whose labor and infrastructure they're profiting off of, not just being minimally taxed by the low-rate nation they're running their profits through. The details of getting that done, though, are what's important here. And it's there that I'm left with a lot more to chew on.

Your questions, answered.

Q: I had a question concerning the United States Postal Service and Louis DeJoy. It seems like DeJoy is doing everything he can to torpedo the USPS, and it feels like there’s nothing that can be done to stop him and save this incredibly important service from becoming solely privatized. Am I wrong? Can the USPS be wrestled from his hands, and is it possible to actually fix it so that it is no longer in jeopardy?

— Jen, Glen Cove, New York

Tangle: This story is actually about to get very hot. By now most Americans have probably noticed the USPS getting a lot slower, and mail service speeds today are somehow back where they were in the 1970s. I've personally experienced the slowdown under DeJoy (and the huge pains that come with it) — anecdotal evidence that matches the data we're getting from USPS and watchdogs who oversee the agency. My own opinion is that the USPS is critical and worth spending a ton of money on, and that DeJoy's appointment (which I was once open to) has been a disaster.

There are now attorneys general in 19 states and the District of Columbia who have filed an administrative complaint asking to block the 19-year budget-cutting plan DeJoy is hoping to implement. The complaint asks the Postal Regulatory Commission to review the plan in detail before rolling it out, and would also allow U.S. Postal Service customers to submit comments during hearings.

DeJoy's plan is a political disaster, as it calls for higher rates, reduced postal office hours and slower service. Given how many Americans across political lines rely on the Postal Service in their day-to-day lives, and DeJoy's ties to former President Trump, you might have expected him to be fired. But that's not something Biden can do easily. Instead, that's up to the governing board of the USPS. Biden got his nominees confirmed to the board this summer, which increases the odds they may replace DeJoy, but so far there has been very little movement there. It's possible they are waiting to see how his plan rolls out (or if it rolls out), but for now this latest challenge is probably the most likely way to stop the changes he's proposed.

A story that matters.

Inflation is hitting levels not seen in 13 years, and analysts are increasingly worried its not going anywhere. Another jump in consumer prices in September sent inflation up 5.4%, according to the Associated Press. Tangled global supply lines continue to create havoc, and the "price of houses, rent, food, gas, electricity, furniture, new cars, TVs and restaurants all jumped," Axios reports. Worse yet, higher prices are rising faster than the pay gains workers are commanding from many businesses. On the other side: clothing prices, car rentals, hotel rooms and airline tickets fell.

Numbers.

- 65%. The percentage of all voters who "somewhat” or "strongly" support raising corporate tax rates to pay for Biden's infrastructure plan.

- 21%. The percentage of all voters who "somewhat" or "strongly" oppose raising corporate tax rates to pay for Biden's infrastructure plan.

- Five. The number of people killed in Norway in a bow and arrow attack.

- 22%. The reduction in new daily Covid-19 cases over the last 14 days, according to The New York Times.

- 52.80%. The highest ever corporate tax rate in the U.S., in 1968.

- 1%. The lowest ever corporate tax rate in the U.S., in 1910.

Don't forget!

If you want to see us tomorrow (and get our edition about Julian Assange), you need to subscribe. You can become a member by clicking the button below!

Have a nice day.

William Shatner, the actor who played James T. Kirk in the original Star Trek series, flew to space yesterday. The 90-year-old joined three other crew members aboard Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin rocket, named New Shepard, and became the oldest person to ever enter space. The entire flight lasted about ten minutes, reaching 65 miles above the earth, where crew members experienced about four minutes of weightlessness. The New Shepard hit a peak altitude of 351,000 feet. "What you have given me is the most profound experience I can imagine," Shatner told Bezos after landing. "I am overwhelmed. I had no idea." NBC News has the story.

❤️ Enjoy today's issue?

📫 Forward this to a friend and let them know where they can subscribe (hint: it's here).

💵 Drop some love in our tip jar.

🎧 Rather listen? Check out our podcast here.

🛍 Love clothes, stickers and mugs? Go to our merch store!

Member comments