I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

We need more debate.

I'm a firm believer that one of the biggest issues in our society — especially politically — is that people who disagree spend a lot less time talking to each other than they should.

Last week, I wrote about how the two major political candidates are dodging debates. Yesterday, I wrote about how a well known scientist (or someone like him) should actually engage Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on his views about vaccines.

In both cases, I've received pushback. There are, simply put, many millions of Americans who believe that minority views — whether it's that the 2020 election was stolen or vaccines can be dangerous or climate change is going to imminently destroy the planet or there are more than two genders — are not worth discussing with the many people who hold those viewpoints. Many of these same people believe influential voices are not worth airing and are too dangerous to be on podcasts or in public libraries or in front of our children.

On the whole, I think this is wrongheaded. I've written a lot about why. But something I hadn’t considered is that people are skeptical about the value of debate because there are so many dishonest ways to have a debate. People aren’t so much afraid of a good idea losing to a bad idea; they are afraid that, because of bad-faith tactics, reasonable people will be fooled into believing the bad idea.

Because of that, I thought it would be helpful to talk about all the dishonest ways of making arguments.

The nature of this job means not only that I get to immerse myself in politics, data, punditry, and research, but that I get a chance to develop a keen understanding of how people argue — for better, and for worse.

Let me give you an example.

I could make the argument that guns make all us safer. To support this argument, I could point to the largest and most comprehensive survey of American gun owners ever conducted, which found that firearms were used in self-defense 1.7 million times per year, proof that guns are a critical aspect of people defending themselves from violence. Similarly, 94% of all mass public shootings since 1950 have happened in gun-free zones, according to a 2018 report — evidence that areas without guns actually invite violence, not prevent it.

Moving from this position, I could argue that any attempt to limit the free flow of firearms will make individuals and society less safe, and that if you are concerned about mass shootings or being able to defend yourself, you should either own a gun or support the right of others to do so.

This would be an argument of omission. Making it requires omitting studies that show owning a gun substantially increases the risk of being killed with a gun, that defensive use cases might be vastly overstated, and that guns are used for violence far more often than they are used to defend oneself. It also requires omitting context on gun-free zones, like the fact that from 1950 to 1990 many states banned or heavily restricted concealed firearms, making essentially any mass shooting during those years one that took place in a gun-free zone. The study cited by the original argument also classified places like military bases as gun-free zones (because guns are restricted for citizens), even though armed officers are stationed there. And, of course, it omits the simple fact that there are more gun deaths in states with more gun ownership.

Now, it's possible that gun ownership can increase safety for certain people in certain scenarios. But in order to make that argument honestly, you'd need to include the evidence above and address it. Many people choose not to when making this argument.

Omitting key information in arguments, or omitting counter-evidence to central claims, is just one bad argument style that is common in politics.

For the purposes of this piece, I’ve identified several others. Below, I'm going to define them, give some recent examples from the news, and then explain why they’re deficient, all with the hopes of making it easier for you to identify them when these argument styles pop up — and why you should be critical of them.

Whataboutism: This is probably the argument style I get from readers the most often. There is a good chance you are familiar with it. This argument is usually signaled by the phrase, "What about...?" For instance, anytime I write about Hunter Biden's shady business deals, someone writes in and says, "What about the Trump children?" My answer is usually, "They also have some shady deals."

The curse of whataboutism is that we can often do it forever. If you want to talk about White House nepotism, it'd take weeks (or years) to properly adjudicate all the instances in American history, and it would get us nowhere but to excuse the behavior of our own team. That is, of course, typically how this tactic is employed. Liberals aren't invoking Jared Kushner to make the case that profiting off your family’s time in the White House is okay, they are doing it to excuse the sins of their preferred president's kid — to make the case that it isn't that bad, isn't uncommon, or isn't worth addressing until the other person gets held accountable first.

None of this is helpful or enlightening. Yes, context is important, and if I'm writing about Hunter Biden's business deals I may reference how other similar situations were addressed or spoken about in the past. But when the topic of discussion is whether one person’s behavior was bad, saying that someone else did something bad does nothing to address the subject at hand. It just changes the subject.

Bothsidesism: Naturally, this is what I get accused of the most. I'd describe bothsidesism as a cousin of whataboutism. Wikipedia defines it as "a media bias in which journalists present an issue as being more balanced between opposing viewpoints than the evidence supports." An example might be presenting a debate about human-caused climate change and giving equal air time to two sides: Humans are causing climate change vs. humans aren't causing climate change.

Given that the scientific consensus on climate change is robust, arranging an argument this way would lend credence to the idea that scientists (or people in general) are evenly divided on the issue, even though they aren't. Today, most of the debate isn’t about whether climate change is real, it’s about how to predict it, address it, prepare for it, and resolve it.

At Tangle, what we try to do to avoid bothsidesism is to represent arguments proportionally with space in the newsletter. For instance, when we covered Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s decision to run for president, we shared one liberal pundit arguing for his candidacy and two liberal pundits arguing against it. Given that roughly one in five Democratic primary voters are saying they’d support Kennedy, this was a bit of an over-representation (we gave this argument one-third of the space on the left), but it was better than totally ignoring Democrats who support him or giving them all the space on the left.

Given its relevance here, I want to reiterate the underlying intent of our format: Grappling with arguments that don’t confirm your existing beliefs. This often requires highlighting opinions that may represent a minority viewpoint, but it’s important to be aware of them to understand the range of views that exist on a given topic.

On the flip side, it’s important to acknowledge when your position is in a small minority. It’s okay to argue for something many people don’t believe, but if you don’t offer sound explanations for why that’s the case, you won’t convince many people of your view.

Straw man arguments: This is another common tactic, and it's one you have probably heard of. A straw man argument is when you build an argument that looks like, but is different than, the one the other person is making — like a straw man of their argument. You then easily defeat that argument, because it’s a weaker version of the actual argument.

For instance, in a debate on immigration, I recently made the argument that we should pair more agents at the border with more legal opportunities to immigrate here, a pretty standard moderate position on immigration. I was arguing with someone who was on the very left side of the immigration debate, and they responded by saying something along the lines of, "The last thing we need is more border agents shooting migrants on the border."

Of course, my argument isn't for border agents to shoot migrants trying to cross into the U.S., which is a reprehensible idea that I abhor. This is a straw man argument: Distorting an opposing argument to make it weaker and thus easier to defeat.

Unfortunately, straw man arguments are often effective as a rhetorical tactic. They either derail a conversation or get people so off-track that their actual stance on an issue becomes unclear. For the purposes of getting clarity on anyone’s position or having an actual debate, though, they are useless.

The weak man: There are different terms for this but none of them have ever really stuck. I like Scott Alexander's term, the weak man, which he describes this way: "The straw man is a terrible argument nobody really holds, which was only invented so your side had something easy to defeat. The weak man is a terrible argument that only a few unrepresentative people hold, which was only brought to prominence so your side had something easy to defeat."

The weak man is best exemplified by the prominence of certain people. For instance, have you ever heard of Ben Cline? What about Marjorie Taylor Greene? I'd wager that most of my readers know quite a few things about Greene, and very few have ever even heard of Ben Cline. Both are Republican representatives in Congress. One is a household name, and the other is an under-the-radar member of the Problem Solvers Caucus. Why is that?

Because Greene is an easy target as "the weak man." Democrats like to use her to portray the Republican party as captured by QAnon, conspiracy theories, and absurd beliefs because they found social media posts where she spouted ridiculous ideas about space lasers and pedophilia rings.

The weak man is largely responsible for the perception gap, the reality in our country where most Democrats vastly misunderstand Republicans and vice versa. For instance, more than 80% of Democrats disagree with the statement "most police are bad people." But if you ask Republicans to guess how Democrats feel about that statement, they guess less than 50% disagree; because the weak man is used so effectively that it distorts our understanding of the other side’s position.

Moving the goalposts: This is one of the hardest ones to spot, but it is critical to entrenching a partisan mindset, and for that reason all too common in politics. When someone or a group of people change the standard of what is acceptable or unacceptable to them in real time, they’re “moving the goalposts” for what needs to be achieved to challenge their ideas.

I actually just called out an example of this in Tangle recently.

Amid the scandal around Donald Trump's handling of classified documents, many of his defenders first alleged the documents he had were likely declassified by him before he left office. Then they argued they might have been classified, but they were probably mementos and other benign things — like letters from foreign leaders. Then they argued that they may have been classified documents, but unless they were something like nuclear or military secrets, raiding his home was unnecessary and overkill.

Then, of course, the indictment alleged that some of the documents found did contain nuclear secrets, military secrets, and other highly sensitive information. That's when The Wall Street Journal editorial board published this whopper: "However cavalier he was with classified files, Mr. Trump did not accept a bribe or betray secrets to Russia."

This is classic moving of the goalposts. We went from “there weren't classified documents” to “they were classified but not that serious” to “they may have been classified but the raid was unjust unless there were nuclear secrets” to "okay, but he wasn’t selling the nuclear secrets to Russia."

Of course, this is not something unique to Trump or conservatives. But this was a potent, recent example of how it works in real time.

Anecdotal reasoning: An anecdote is a short story about something that really happened. Anecdotal reasoning is using that real event to project it as the norm, and then make an argument that your lived experience is representative.

Frankly, I’m hesitant to include this one in the context of today’s newsletter, because I do think politics are personal — and personal experiences should be shared and considered. They are often enlightening, and anyone who reads Tangle knows I regularly lean into personal experience. But they can also be a trap. Anecdotal arguments are dangerous because they can prevent people from seeing that their experience might be the exception rather than the rule.

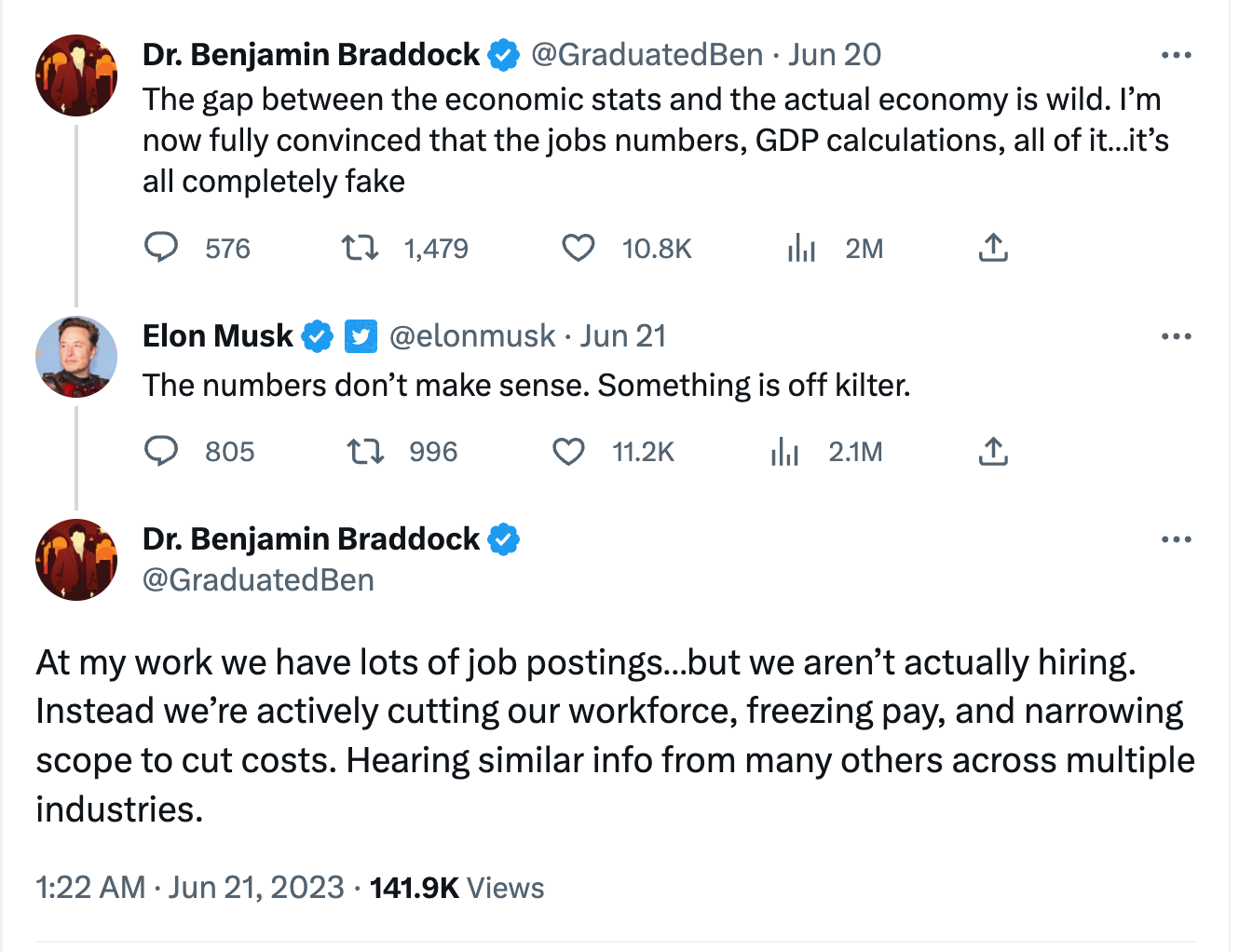

We actually just had a great example of this, too. As you may have heard, unemployment is currently near an all-time low. At the same time, though, the tech sector (which is a fraction of the economy) has been experiencing a lot of layoffs and downsizing. This has left many people in tech concluding that the job numbers are somehow wrong or being fudged. Take a look at this exchange on Twitter:

This is a classic example of an anecdotal argument. Because personal experiences are so powerful, we struggle to see beyond them. While anecdotes can add color or create context, they shouldn't be used to extract broad conclusions.

Prove a negative: This might be the most frustrating style of argument there is. The "prove a negative" argument is when someone insists that you prove to them something didn't happen or isn't true, which implies that they have evidence something did happen or is true — but they don’t actually present that evidence.

For instance, if I asked you to prove that aliens don't exist, you might have a hard time doing it. Sure, you could argue that we don't have an alien body locked up in some government facility (or do we?), but you’d have a hard time listing the contents of every government facility. And if you could somehow do that, you haven’t proved that aliens don't exist at all, or even that they've never been to Earth. But the burden of proof isn't on you to show me that aliens don't exist, it's for me to show you evidence that they do.

This was, in my experience, one of the most frustrating things about some of the early claims that the 2020 election was stolen. A lot of people were alleging that Dominion Voting Systems was flipping votes from Trump to Biden, and then insisting that someone must prove this didn't happen. But the burden of proof was not to show that it didn't happen (proving a negative), it was to show that it did happen. Which nobody ever did.

When making an argument, insisting someone prove a negative is always a hollow way to approach an issue. If we want to debate something, there first needs to be an affirmative claim to discuss, and then evidence to support that claim. Absent that, whatever can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence.

Circular reasoning: I would never make one of these bad arguments. And because I wouldn’t make a bad argument, this argument I’m making isn’t a bad argument. And I am not a person who makes bad arguments, as evidenced by this argument I’m making, which isn’t a bad argument.

Exhausting, right? That’s an example of circular reasoning, which uses two claims to support one another rather than using evidence to support a claim. This style of argument is pretty common in supporting broad-brush beliefs. Here are a few examples:

- Women make bad leaders. That’s why there aren’t a lot of female CEOs. That there are not a lot of female CEOs proves that women are bad leaders.

- People who listen to Joe Rogan’s podcast are all anti-vaccine. I know this because RFK Jr. was recently on the podcast spreading lies about vaccines, which proves that his anti-vaccine audience wants to hear lies about vaccines.

- The media is lying to us about the election in 2020 getting stolen. If the media were honest, they’d tell us that the election had been stolen. And the fact that the dishonest media isn’t telling us that is more proof that the election was stolen.

Circular arguments are usually a lot harder to identify than this, and because they’re self-enforcing are often incredibly difficult to argue against. In practice, there are usually a lot more bases to cover that reinforce a worldview, and it can be incredibly difficult to address one claim at a time when someone is making a circular argument.

Of course, these aren't all the ways to make dishonest arguments. There are a lot of others.

There is the "just asking questions" rhetorical trick, where someone asks something that sounds a lot like an outlandish assertion, and then defends themselves by suggesting they don't actually believe this thing — they're just asking if maybe it's worth considering.

There is "black and white" arguing, where an issue becomes binary this or that (is Daniel Penny a good samaritan or a killer?) rather than a complex issue with subtleties, as most things actually are. There’s ad hominem argument, when someone attacks the person ("RFK Jr. is a crackpot!") rather than addressing the ideas ("RFK Jr. is wrong about vaccine safety because..."). There is post hoc — the classic correlation equals causation equation ("The economy grew while I was president, therefore my policies caused it to grow.") There are the slippery slope arguments ("If we allow gay marriage to be legal, what's next? Marrying an animal?") and false dichotomy arguments (like when Biden argued that withdrawing from Afghanistan was a choice between staying indefinitely or pulling out in the manner that he did). There is also the “firehose” trick, which essentially amounts to saying so many untrue things in such a short period of time that refuting them all is nearly impossible.

In reality, a lot of the time we’re just talking past each other. There is one particularly annoying example of this I run into a lot, which is when people interpret what you said as something that you didn't (close to a straw man argument), or ignore something you did say and then repeat it back to you as if you didn't say it. This actually just happened to me this morning on Twitter (of course).

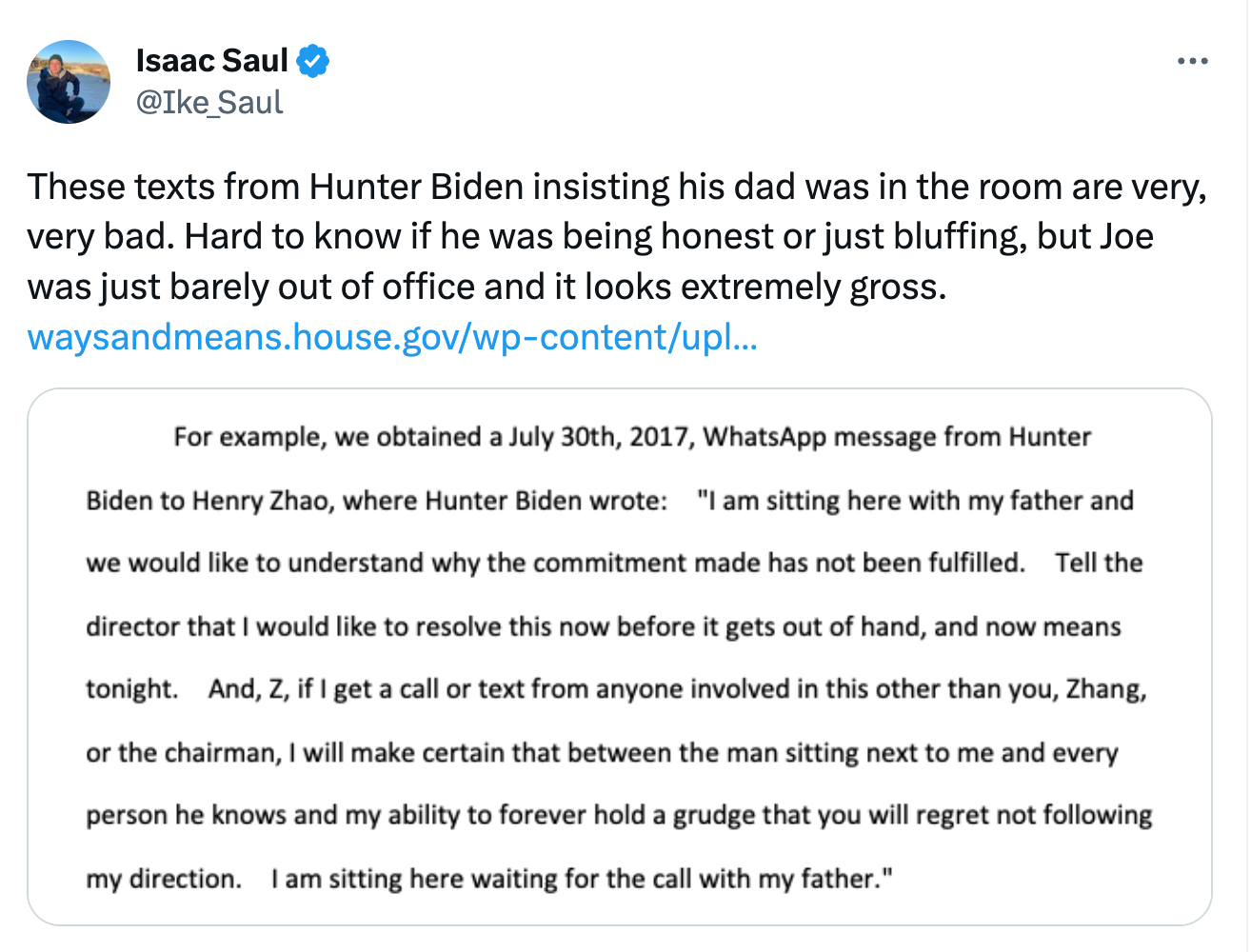

It started when news broke yesterday about an IRS whistleblower testifying on damning text messages from Hunter Biden that were obtained through a subpoena. I tweeted out a transcript of the message Hunter Biden purportedly sent to a potential Chinese business partner. In the message, Hunter insists his father is in the room with him, and they are awaiting the call from the potential partner. Obviously, this would undercut President Biden's frequent claims that he had nothing to do with Hunter's business dealings.

I tweeted this:

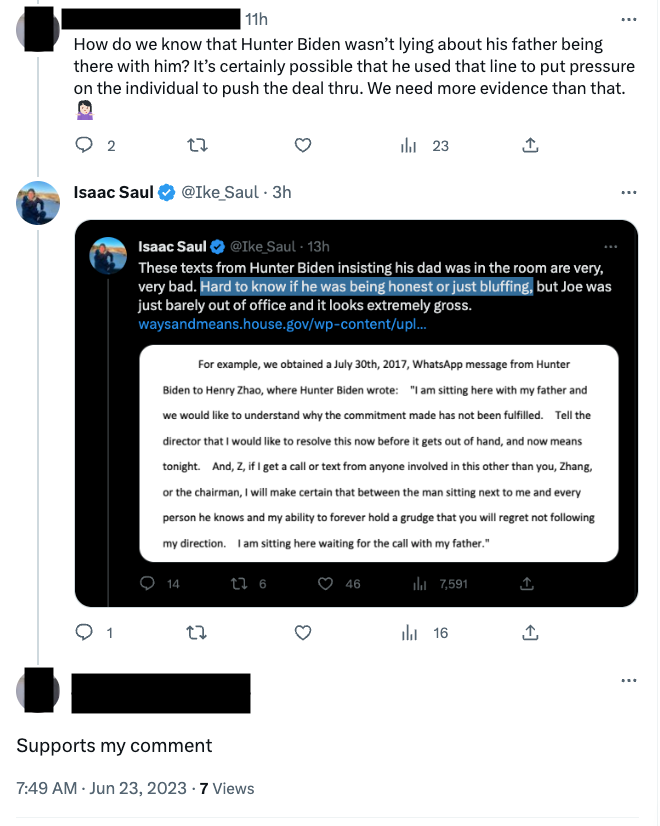

"It’s a WhatsApp message, whose to say Joe was even in the room?" one user responded.

"Addicts tend to lie a lot, don’t they? Steal from grandma and such?" another person said.

"Hunter was a crack addict at the time. A crack addict lying for money??? No!!" someone else wrote.

Of course, I aired this possibility right there in my tweet. Again, emphasis mine, I said: "These texts from Hunter Biden insisting his dad was in the room are very, very bad. Hard to know if he was being honest or just bluffing, but Joe was just barely out of office and it looks extremely gross."

But as people, we often come into conversations already knowing what point we want to make, and we’ll try to make it regardless of what the other person said. In one case, when I pointed out that I had literally suggested this very thing in my tweet, someone responded that it buttressed their point — as if I had never said it all.

Of course, just as important as spotting these rhetorical tricks is being sure you are not committing them yourselves. Dunking on bad ideas, styling ideas few people believe as popular, or using anecdotes to make broad claims are easy ways to “win” an argument. Much more difficult, for all of us, is to engage the best ideas you disagree with, think about them honestly, and explain clearly why you don't agree. And even more difficult is to debate honestly, discover that the other person has made stronger arguments, adapt your position and grow. Because of the current media landscape, arguments that don’t contain these bad-faith tactics aren’t always the ones that end up in Tangle — but they are the kind of arguments I aspire to employ myself.

And I’d love to get your help. In the coming week, please write in if you see an argument in Tangle that employs any of the above-mentioned tactics. I want to commend the readers who can spot a deficiency, maybe in a source we cite but especially in an argument I’m making. Something I always want to do with Tangle is to support the best arguments, and that only happens if we can call out the bad ones.

Enjoyed today's newsletter?

- Drop something in the tip jar

- Forward this email to friends

- Write in with thoughts!

As you (hopefully) know by now, we are hosting an event in Philadelphia on August 3. The event will be held at Brooklyn Bowl Philadelphia, and in partnership with our awesome venue we have decided to do a contest. We’re offering an opportunity to land two VIP seats in the first two rows, a pre-show VIP meet-and-greet, and free Tangle merchandise, and all you have to do is submit your email address to participate. You can join the fun by clicking here. We're only running this promotion until Monday night!

New video.

We're up with a fresh new interview video on YouTube! I was thrilled to sit down with Philip Wallach, who spoke about the problems in Congress, how to fix them, and how they tie into the history of the institution.

Member comments