I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, ad-free, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum — then “my take.” You’re receiving this Friday edition because you’re a paying member of Tangle. It’s behind a paywall, but feel free to forward it to friends or share on social media. If someone sent you this, they’re asking you to subscribe. You can do that by clicking here.

Today’s read: 20 minutes.

We’re going deep on the arguments for and against the Electoral College — and how we ended up with this wild system in the first place.

When all the votes in the 2020 election are finally counted, Joe Biden will have netted about seven million more than his opponent, President Donald Trump.

In many elections across the globe, and in state contests in the U.S., this would be a decisive defeat. But in America’s presidential race, the election felt and indeed was much closer than the 4.5% margin of the popular vote. That’s because our presidential election is not decided by the popular vote, but by the Electoral College — a system that awards points to each candidate based on the value of individual states.

The presidential electors in America are unique; the U.S. is the only country that has a system where a body of electors’ sole function is to choose the president. Other democratic republic nations have similarly indirect elections, but in those countries the job of choosing the president or national leader is given to the national legislatures. In Germany, for example, “the president is elected by the 630 members of the Bundestag together with 630 delegates chosen by the state parliaments,” as Pew describes it.

For all our griping, the U.S. system is actually pretty straightforward. For example, Pennsylvania has 20 electoral college votes because its congressional delegation is made up of 20 people — two senators and 18 representatives in the House.

Americans in every state vote. Each state (with the exception of Nebraska and Maine but including Washington, D.C.) casts all of its Electoral College votes to the state’s popular vote winner. If candidate A gets more votes than candidate B in Pennsylvania, then all 20 electors in Pennsylvania cast their votes for candidate A. Faithless electors, or electors who buck the popular votes of their states, have become a hot topic in this election, as they were in 2016. But they are exceedingly rare, and most states have laws to punish or remove faithless electors — laws that have been upheld constitutionally in recent Supreme Court rulings.

Nebraska and Maine each cast two votes for whichever candidate wins the popular vote and one electoral vote according to the popular result in each of their congressional districts. This difference is a good reminder that each state in America — as dictated by the Constitution — controls its own elections even while operating in the larger federal system.

And that’s it. You vote in your state, your state’s electors award your state’s votes to the popular vote winner, and the first candidate to get 270 electoral college votes wins the presidency. For all the centuries of debate, it really is that simple. Yet, this system has been controversial and evolving since its inception, and in recent years the debate over the electoral college has only intensified.

In general terms, many Democrats and liberals have taken the position that the electoral college puts them at a decisive disadvantage and that it undermines the will of the majority. Despite happening just five times in all of American history, twice in the last 20 years the loser of the national popular vote has won the presidency by winning the electoral college (George W. Bush in 2000 and Trump in 2016). This year, despite losing the national popular vote by more than seven million votes, President Trump only lost the Electoral College by about 104,000 votes across Pennsylvania, Georgia and Arizona, which could easily have changed the outcome. Put another way: President Trump lost the popular vote by 67 times the number of votes he lost the electoral college by.

Republicans and conservatives have, conversely, argued that the electoral college preserves the voices of less populated states, allows for individual state representation and stays true to the framework laid out by the founders. It also protects against federal overreach by keeping states — and not the federal government — in control of their elections. In fact, being a bulwark against the majority is precisely the point of the Electoral College, and is why our system has been so effective. Conservatives are keen on reminding detractors that we are not a pure democracy, but a constitutional or democratic republic — attempting to balance power between state and federal governments.

As in many other arenas, the partisan rancor over our voting system has divided the nation. 61% of Americans support a constitutional amendment to use the popular vote to determine the presidential winner. 89% of Democrats, 68% of independents and just 23% of Republicans want to codify the popular vote to elect the president. While there are many arguments to cover in this debate, there is also some fascinating history behind how the Electoral College came to be and why we still have it now. We’ll go through that first, and then dive into the more popular and compelling arguments from each side.

History.

As with most major moments in American history, the creation of the Electoral College came with a lot of debate and nuance.

When the founding fathers met for the Constitutional Convention, creating a mechanism to pick the president was a major hurdle. James Wilson wrote in 1787 that the delegates had been “perplexed with no part of this plan so much as with the mode of choosing the president.” Wilson argued that the people should elect the president directly. James Madison argued that — because of the spread of suffrage — the North had more voters than the South, meaning the South would have no voice. Wilson’s proposal was shot down by a 12 to 1 vote.

When they reconvened, some delegates argued Congress should select the president. They were, after all, already chosen themselves by the voters. It was a popular idea. Members had the power to pick the president themselves and “avoid the excesses of democracy,” as one put it. At the time, this indirect election method was common. Until 1913 U.S. senators were chosen by state legislatures, not by the people (imagine that!). But the issue with Congress choosing the president was that it blew up an entirely different part of our framework: the separation of powers. How could Congress, which was supposed to be a check on the executive branch, also be the body to choose the head of the executive branch?

James Wilson’s solution: electors. If neither the people nor Congress could choose the president directly, then an independent body should handle it. The people would elect delegates to an Electoral College, who would then deliberate on behalf of the people in order to choose the president.

Of course, this too created issues. Most obviously: how many delegates would each state get? The founders decided the number of delegates would be determined by population representation (essentially the same concept we have today, as explained above). But at the time, the number of representatives was determined by allocating one member of Congress for every 40,000 people in a state. In the south, where slavery was more prominent, slaveowners wanted to count slaves as part of their populations, even though slaves couldn’t vote (at the time, very few people could vote besides white, land-owning men). The goal was obvious: counting slaves gave them more political power.

This tension created the notorious three-fifths compromise, where one slave was counted as three-fifths of a free citizen. In that way, the Electoral College was very much a compromise to favor slave owners — a concession to give them more power on behalf of the people they owned, power they got to exercise while their slaves did not. Consequently, this agreement also created the need for a census. If we were going to pick the president based on electors, and the number of electors would be based on representation in Congress, and representation would be based on population, then we surely needed to know the population. And that’s when we formally began counting who lived in the U.S. through the Census Bureau. The first federal census, conducted in 1790, counted 3.9 million people, including 700,000 slaves.

With slave-owning states holding disproportionate representation, their power was evident immediately. Virginia, for example, had the same free population as Pennsylvania — but it had three more seats in the House and six more electors when three-fifths of the slave population was added. That had an impact, too, as seen clearly in this astounding historical fact: for 32 of the first 36 years under this system, our president was a slave-owning Virginian. John Adams is the only exception. Today, this historical reality is very much part of why the roots of the Electoral College are considered to be corrupt by so many people.

When it was all said and done, the language creating the Electoral College was finalized in Article 2 of the Constitution:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the Seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted.

The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately choose by Ballot one of them for President; and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner choose the President. But in choosing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representatives from each State having one Vote; a quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all the States shall be necessary to a Choice.

In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall choose from them by Ballot the Vice-President.

The Congress may determine the Time of choosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

Where we are now.

While the electoral college picks the president, we don’t pick the electors. That’s still done by the state legislatures. In the beginning, electors voted for two presidential candidates — and the one who got the second most votes became vice president. This system imploded when two-party politics became popular.

In 1796, Federalists wanted John Adams as president and Thomas Pinckney as vice president — but the results ended up with Adams in the lead, Thomas Jefferson in second place with sixty-eight votes, and Pickney with only fifty-nine. Federalist electors were supposed to cast one vote for Adams and their second for Pickney, but many cast it for Jefferson instead. That left Adams as president and Jefferson as his vice president, which, as Jill Lepore writes in her book These Truths, came “to the disappointment of everyone.” In 1800, a similar situation occurred: Republican electors were supposed to vote for Jefferson and Burr, but one elector was supposed to not vote for Burr, so that Jefferson would win by one and become president and Burr his vice president.

But that one elector forgot to follow through. The result was a tie — which sent the presidential race to the House and nearly created a constitutional crisis (Congress eventually organized behind Jefferson). The 12th amendment was then passed in 1804 to separate the presidential and vice-presidential processes, so electors could vote for them separately.

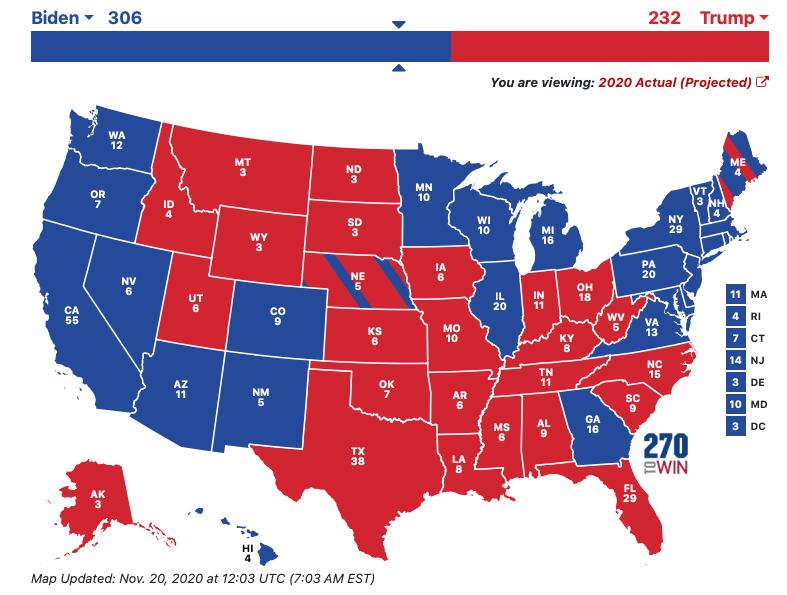

Details like this have been ironed out over the 200-plus years since. Today, states all appoint their electors based on popular vote — nearly all are awarded in all-or-nothing contests (again: Nebraska and Maine being the exceptions). In this year’s election, Joe Biden won 306 electoral votes to Donald Trump’s 232 (remarkably, the same split Trump beat Hillary Clinton by in 2016, though he did it by winning different states and while losing the popular vote).

As of Wednesday afternoon, all 50 states and Washington, D.C. had certified their election results. After certifying results, every state will submit Certificates of Ascertainment — the names of its electors and their election results — to the Archivist of the United States “as soon as practicable.”

States have until Monday, December 14 to submit this certificate, the same day that the Electoral College meets. The name “Electoral College” is a bit misleading since electors meet state by state and never actually assemble in one place. At these meetings, electors record their votes on, and sign, six “Certificate of Votes”, then pair each certificate with a Certificate of Ascertainment, and send one pair each to the President of the Senate (Mike Pence), the Chief Judge of the Federal District Court where the electors meet, to the Archivist of the United States, and to their state’s Secretary of State.

The Archivist transfers their copies of the Certificates of Votes to the House and Senate on or before January 3, the date the new Congress is set to assemble. Then, on January 6, Congress meets in a joint session to count the votes. Mike Pence, President of the Senate, will preside over the count and the candidate who gets 270 votes or more is elected president. The next and final step is for the President-elect and Vice-President-elect to take the oath of office at their inauguration at noon on January 20th.

There’s always the possibility of a few hiccups along the way. First, an elector could try to vote for a different candidate than the one they are pledged to according to their state’s election results: the “faithless elector.” Back in July, the Supreme Court ruled that states can disqualify or fine electors who stray from their pledges. More than 30 states have these rules, including swing states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Arizona. Electors are unlikely to break with their state’s mandate, and even if some did, Biden’s 306 to 232 lead stands no chance of being overturned.

Another possible bump in the road could come during the vote-counting process in Congress. If a Senator and Representative file an objection to a state’s votes, the objection would go to each chamber separately for consideration. Given that Democrats control the House, that chamber would certainly shoot the complaint down and the votes would be counted.

To summarize these technicalities: Joe Biden is going to be inaugurated as president on January 20. All that remains is the formal process.

Against.

The case against the Electoral College is pretty well known. For one, it gives an advantage to rural states with far fewer residents, and it distorts the power of the individual vote. Most obviously, a single person voting in Wyoming has a more powerful vote than a single person voting in California. It also “compels candidates to concentrate their efforts on the few states that are competitive, ignoring the interests of large regions of the country,” as Seymour Spilerman wrote in The Washington Post. And, of course, it was created as part of a concession to uphold the power of slave owners, one of the most abhorrent practices in U.S. history.

In 2016, after Hillary Clinton won the popular vote but lost the election, The New York Times editorial board published what is now one of the most widely shared arguments against the Electoral College.

“And so for the second time in 16 years, the candidate who lost the popular vote has won the presidency,” they wrote. “Unlike 2000, it wasn’t even close. Hillary Clinton beat Mr. Trump by more than 2.8 million votes, or 2.1 percent of the electorate. That’s a wider margin than 10 winning candidates enjoyed and the biggest deficit for an incoming president since the 19th century. Yes, Mr. Trump won under the rules, but the rules should change so that a presidential election reflects the will of Americans and promotes a more participatory democracy.”

“The Electoral College, which is written into the Constitution, is more than just a vestige of the founding era; it is a living symbol of America’s original sin,” the board added. “When slavery was the law of the land, a direct popular vote would have disadvantaged the Southern states, with their large disenfranchised populations. Counting those men and women as three-fifths of a white person, as the Constitution originally did, gave the slave states more electoral votes. Today the college, which allocates electors based on each state’s representation in Congress, tips the scales in favor of smaller states; a Wyoming resident’s vote counts 3.6 times as much as a Californian’s. And because almost all states use a winner-take-all system, the election ends up being fought in just a dozen or so ‘battleground’ states, leaving tens of millions of Americans on the sidelines.”

In Vox, Sean Illing made a similar argument against the Electoral College.

“One of the biggest problems with American democracy is that it’s not democratic,” he wrote. “Two of the last five presidents were elected despite losing the popular vote, more than half the Senate is elected by roughly 18 percent of the population, and voting districts are increasingly gerrymandered in ways that disenfranchise the people who live there. Our process for choosing the president, the Electoral College, is probably the strangest and most explicitly anti-democratic feature of the American political system. It was conceived in part as a firewall against majority will in case the mob ever elected someone grotesquely unqualified for the office. (It, uh, didn’t work.)”

“Whatever the case, there’s no denying that the Electoral College is anti-democratic,” he added. “According to Democratic data scientist David Shor, ‘The Electoral College bias is now such that realistically [Democrats] have to win by 3.5 to 4 percent in order to win presidential elections.’”

In an interview with Illing, Jesse Wegman, who wrote the book Let The People Pick The President, noted that “you had the immovable obstacle of slavery and ensuring that the slave-holding states didn’t unravel the whole process. James Madison himself said during the middle of the convention that ‘the popular vote is the fittest way to elect a president,’ but that the South wouldn’t go for it. And he says this more than once. So it’s clear that the Founders knew the slave states had a ton of leverage.”

In The New Yorker, Steve Coll argued that this is not some ancient relic of racism — the Electoral College’s power is very much tied to race today.

“James Madison, who helped conceive the Electoral College at the Constitutional Convention, of 1787, later admitted that delegates had written the rules while impaired by ‘the hurrying influence produced by fatigue and impatience.’ The system is so buggy that, between 1800 and 2016, according to Alexander Keyssar, a rigorous historian of the institution, members of Congress introduced more than eight hundred constitutional amendments to fix its technical problems or to abolish it altogether,” Coll wrote. “In much of the postwar era, strong majorities of Americans have favored dumping the College and adopting a direct national election for President. After Kefauver’s hearings, during the civil-rights era, this idea gained momentum until, in 1969, the House of Representatives passed a constitutional amendment to establish a national popular vote for the White House. President Richard Nixon called it ‘a thoroughly acceptable reform,’ but a filibuster backed by segregationist Southerners in the Senate killed it.”

“That defeat reflects the centrality of race and racism in any convincing explanation of the Electoral College’s staying power,” Coll added. “In the antebellum period, the College assured that slave power shaped Presidential elections, because of the notorious three-fifths compromise, which increased the electoral clout of slave states. Today, it effectively dilutes the votes of African-Americans, Latinos, and Asian-Americans, because they live disproportionately in populous states, which have less power in the College per capita. This year, heavily white Wyoming will cast three electoral votes, or about one per every hundred and ninety thousand residents; diverse California will cast fifty-five votes, or one per seven hundred and fifteen thousand people.”

For.

The case for the Electoral College is less well known, given that the loudest voices right now seem to oppose it. But it’s been a remarkably stable argument over time: the Electoral College preserves the power of small states against a single, heavily populated outlier state — like, say, California. It also ensures the separation of state and federal power. States run and control their own elections, recounts and rules, without the federal government taking control.

“First, the Electoral College forces candidates to appeal to a wider range of voters,” Allen Guelzo wrote in National Affairs. “A direct, national popular vote would incentivize campaigns to focus almost exclusively on densely populated urban areas; Clinton's popular-vote edge in 2016 arose from Democratic voting in just two places — Los Angeles and Chicago. Without the need to win the electoral votes of Ohio, Florida, and Pennsylvania, few candidates would bother to campaign there. Of course, the Electoral College still narrows the focus of our elections: Instead of appealing to two states, candidates end up appealing to 10 or 12, and leave the others just as neglected. But campaigning in 10 or 12 states is better than trying to score points in just two.”

“Another unsought benefit of the Electoral College is that it discourages voter fraud. There is little incentive for political parties to play registration or ballot-box-stuffing games in Montana, Idaho, or Kansas — they simply won't get much bang for their buck in terms of the electoral totals of those states. But if presidential elections were based on national totals, then fraud could be conducted everywhere and still count; it is unlikely that law enforcement would be able to track down every instance of voter fraud across the entire country.

“A final unforeseen benefit of the Electoral College is that it reduces the likelihood that third-party candidates will garner enough votes to make it onto the electoral scoreboard,” he added. “Without the Electoral College, there would be no effective brake on the number of ‘viable’ presidential candidates. Abolish it, and it would not be difficult to imagine a scenario in which, in a field of dozens of micro-candidates, the ‘winner’ would need only 10% of the vote, and would represent less than 5% of the electorate. Presidents elected with smaller and smaller pluralities would only aggravate the sense that the executive branch governs without a real electoral mandate.”

Others, like Seymour Spilerman, have made the case that a national popular vote would destroy election integrity and give unchecked power to incumbent presidents.

“By partitioning the popular vote among 51 constituencies (50 states plus the District of Columbia), the electoral college structure serves to restrict vote recounts in close elections to a very few states — just the ones that are closely divided in the popular tally and have sufficient electoral votes to affect the outcome,” he wrote. “The consequence of this vote partitioning can be appreciated in the standoff between George W. Bush and Al Gore in 2000. The electoral vote was closely divided, but the outcome was in dispute only in Florida — which had 25 electoral votes then — and the recount was limited to that state. At the national level, the popular vote was also close: Gore led Bush by 0.5 percent of the vote. Had the president been determined by the national popular vote, a nationwide recount would have been likely, requiring tabulation of the 101 million votes cast in the country, along with a consideration of the rejects, with their hanging chads, questionable signatures and issues of voter identity; all this would have taken place against a background of 51 different sets of rules on electoral matters.”

In fact, Spilerman argues, a national popular vote would inspire “strategies that have sprung up in recent years with the objective of diminishing voter turnout — such as the exclusion of felons, burdensome identification laws, challenges to mail-in voting,” he said. “Up to now, manipulations of this sort have affected the presidential contest mainly through their presence in the states that are ‘in competition’ and can influence the election outcome. However, if the electoral decision were to be based on the national popular vote, we can expect such laws, along with outright vote tampering, to be instituted more extensively, especially in states dominated by a single political party, since the institutional arrangements for ensuring a fair contest are weakest in such settings.

“The electoral college is a flawed anachronism, and its failings are manifest. Understandably, people tend to focus attention on the vexing deficiencies of the current system, since we are familiar with — and exasperated by — them. But any change would involve a trade-off. And we should consider the benefits of the current, imperfect system as well as the potential downside of any suggested replacement.”

In a Wall Street Journal article written after this election, Steven Landsburg argued that if the left is actually worried about a coup — abolishing the electoral college is a good way to do it.

“Imagine a future presidential election in which the incumbent refuses to concede and enlists the full power of the federal government to overturn the apparent democratic outcome,” he wrote. “Now imagine that the election in question is actually run by a federal agency or by some nationwide quasi governmental authority charged with collecting and aggregating the results from all 50 states. I don’t know about you, but I might worry a bit about the pressure that could be brought to bear on that single authority. I might worry a bit about the objectivity of the attorney general and the federal election commissioners who would be in a position to ramp up that pressure.”

A solution.

One of the more recent developments in this debate is the National Popular Vote interstate compact. This compact actually plays within the bounds of the Constitution, which allows state legislatures to tell their electors how to vote. 15 states and the District of Columbia, which represents 196 electoral votes, have passed legislation that would ensure electors vote only for the winner of the national popular vote. If enough states sign off that they hit the threshold of 270 electoral college votes, the pact would go into effect and ensure the national popular-vote winner becomes president regardless of what the remaining states decided.

Plenty of people have written in opposition to the compact, including a recent Wall Street Journal letter making a similar case to Guezlo’s: the compact could create such a massive presidential field that someone with 30% (or less) of the popular vote could win the presidency.

My take.

First, I just want to point out clearly that party preference on the Electoral College is almost entirely based on how it’s currently impacting that party’s election odds. The debate over the Electoral College is, perhaps, the most obvious example of how cynical partisans are — and how partisan bias impacts the way we view something.

In 2004, when George W. Bush narrowly defeated Democratic candidate John Kerry in the presidential election, he won the popular vote by 3 million. Despite that, if just 60,000 votes had gone the other way in Ohio, Kerry would have won. This was an election where the electoral college benefited Democrats, and in response, many liberals were penning op-eds defending the Electoral College — and many Democratic politicians saw it as a strength. Just four years prior, The New York Times editorial board wrote an op-ed defending the Electoral College.

In 2012, when early returns were coming out and it looked as if Barack Obama was going to win the election but lose the popular vote to Mitt Romney, Donald Trump tweeted this:

Similarly, Republicans that year floated the preposterous idea of changing the laws in Pennsylvania to allocate electoral votes by Congressional districts — because they knew Obama would win the popular vote but lose plenty of Republican districts. At the time, Republicans controlled both the state legislature and the governorship, and some were perfectly willing to blow up the traditional way the Electoral College functioned to win an election.

Four years later, as a presidential candidate, Trump and his supporters defended the electoral college as a Constitutional miracle (though he continued to insist fraud was the only reason he lost the popular vote). All that is to say: much of the partisan wrangling over this question — and the fact it has become a left-right divide — is purely a product of how the Electoral College has favored Republicans and negatively impacted Democrats in the last two elections.

When thinking about the debate, to me, that means I need to step out of the historical context of “who is this hurting” and look instead at the question of “is this argument actually accurate?” When approaching it this way, a trend emerges, and that trend is that most of the popular present-day arguments in support of the Electoral College don’t hold up.

Perhaps the most cited of these arguments is that if we moved to a direct popular vote, cities would determine the president. This defies the actual math of what we’re looking at. The 50 biggest cities in the U.S. make up just 15 percent of the total population — that’s not a majority. In fact, rural America also constitutes just about 15 percent of the population. And while cities tend to break about 60-40 in favor of Democrats, rural areas tend to break about 60-40 in favor of Republicans. In most elections, this comes out as a wash.

The idea that New York City or Los Angeles would be picking the president also is detached from reality. And you don’t have to think nationally, just look at the state level: New York had a Republican governor from 1995 to 2006 and has had a Democratic governor since — though he’s one of the most conservative Democratic governors in the country. New York City moved toward Trump this year. Even in the state with the most populous liberal city in America, Republicans still win elections. If New York City can’t consistently swing New York state elections, how could it sway national elections?

California, which is supposed to be a liberal wasteland, accounted for six million votes for Donald Trump this year. That’s more than Texas or Florida. That’s more than Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee and Arkansas combined. Why should California Republicans be excluded in their support for Trump, when there are more of them than Republican voters in the states we think of as traditionally red?

There’s also the idea that the Electoral College preserves the importance of smaller, forgotten states. But does it? How is that going? There are 13 states with three or four electoral college votes. Only one of them — New Hampshire — ever gets any attention in today’s elections. Maine and Nebraska do too, though they’re afterthoughts, and the battles are only for their single congressional district Electoral College votes. When was the last time you saw campaign battles in Montana? Vermont? North Dakota? Idaho?

Montana is a great illustration. About 600,000 people voted there in 2020. That is more than the popular vote margin in 2000 and 1968, elections that gave us George W. Bush and Richard Nixon. How would having an election by popular vote make Montana less important than it is now?

As it stands, there are about 11 states that actually matter, the same ones you hear about nonstop: Florida, Texas, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Arizona, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Georgia and Nevada. How has the Electoral College preserved the value, voice and worth of smaller, more rural America when 39 of the 50 states are basically ignored during a presidential election?

Imagine for a moment that I was a state governor and wanted to propose a change to our election system. My proposal is that instead of giving our electoral college votes to the popular vote winner of the state, I want to give our electoral college votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the most counties. I justify this new proposal by arguing that county elections are each different and that this proposal is a bulwark against heavily populated counties and state rule.

This year, Joe Biden won 3,459,923 votes to Donald Trump’s 3,378,263 votes in Pennsylvania — about an 81,000 vote difference. But Trump won 54 of the 67 counties in Pennsylvania, so under my new rule as governor, we award all our votes to Donald Trump. Would this system be fair? Would you accept it as a resident of Pennsylvania? Of course not — the idea that Trump winning 54 out of 67 counties is more important than losing the popular vote is absurd on its face. But it’s really not much different than dividing states up inside the U.S. as a whole.

It seems to me that, from a representation standpoint, nearly all the arguments made in favor of the Electoral College are actually backward. Rural voters would have the same power in a national popular election as urban voters, as they make up nearly the same proportions of the electorate. They’d be less ignored than they are now, given that most red, rural states are seldom visited by a presidential candidate anyway. And smaller states that are a complete afterthought because of their electoral college value would become more important, not less important, in a national popular vote election.

But none of this solves the problem of holding the actual election itself. The argument that a national election would create more chaos than we have now is, perhaps, the single best argument for preserving the electoral college. Many of these arguments were written before this year’s election, but imagine the case that could be made after the last month. Imagine a world where Donald Trump, contesting the results of the election, did not have to go through the states to overturn results but instead had a federal government body, or official, that could impose its will on his behalf.

Imagine, as others have, a case where the national popular vote was within 100,000 or even 10,000 votes. Imagine the chaos of a full, 50-state recount in an election as divisive as the one we just witnessed. What would happen to the country? How could an incumbent leverage their power to change the outcome? How could the Supreme Court review challenges from a dozen, let alone 40 or 50 states, all with different election laws? What would we do in the weeks or months with no clear outcome?

All this leads me to an unsatisfying but realistic conclusion: as it stands, the Electoral College is grossly unfair and completely counterproductive for most of its stated purpose. It both gives voters in some states more power than voters in others while simultaneously making some 80% of the states in America an afterthought. The arguments in defense of it — that it prevents cities from ruling or preserves the importance of smaller states — fall apart with a little bit of math and the simple exercise of looking around.

But no perfect plan to fix it exists. The simplest solution would be to change nothing about our elections except the fact that, when the votes are all tallied and reported, we add them up and pick a popular vote winner. But then we’d need universal laws across the states to formalize the elections. This would require both federal rule and federal oversight. And if the federal government is deciding how states run elections, and then overseeing those elections, the ruling party — the executive branch — suddenly has more control over the outcome than a challenger. This is already an issue in the form of gerrymandering, but we’d essentially be nationalizing that problem. It’d also put us back to square one where we were 220 years ago: we’d face the issues of separating the powers of the federal government and our state governments.

So what then? I’m really not sure. Our system seems perfectly broken and totally stuck all the same. The reasons for changing it are compelling, far more compelling than for keeping it, but the result of changing it could leave us with a more chaotic and corrupt system altogether. If I were starting anew, the national popular vote would be a no-brainer. But to change it now has the ripple effect of potential new dangers and new flaws — and so far a reassuring solution seems elusive.

Seth Moskowitz contributed to the reporting of this piece.

Thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed this wholly unsatisfying take, feel free to forward this email to friends or post Tangle on social media (you can ignore the footer suggesting otherwise). Also, in case you missed it, Tangle launched a merchandise store this week — with slick hoodies, t-shirts, pullovers and even baby onesies, all right in time for the holidays. You can check out the store by clicking here. And you can share this post by clicking the button below:

Member comments